|

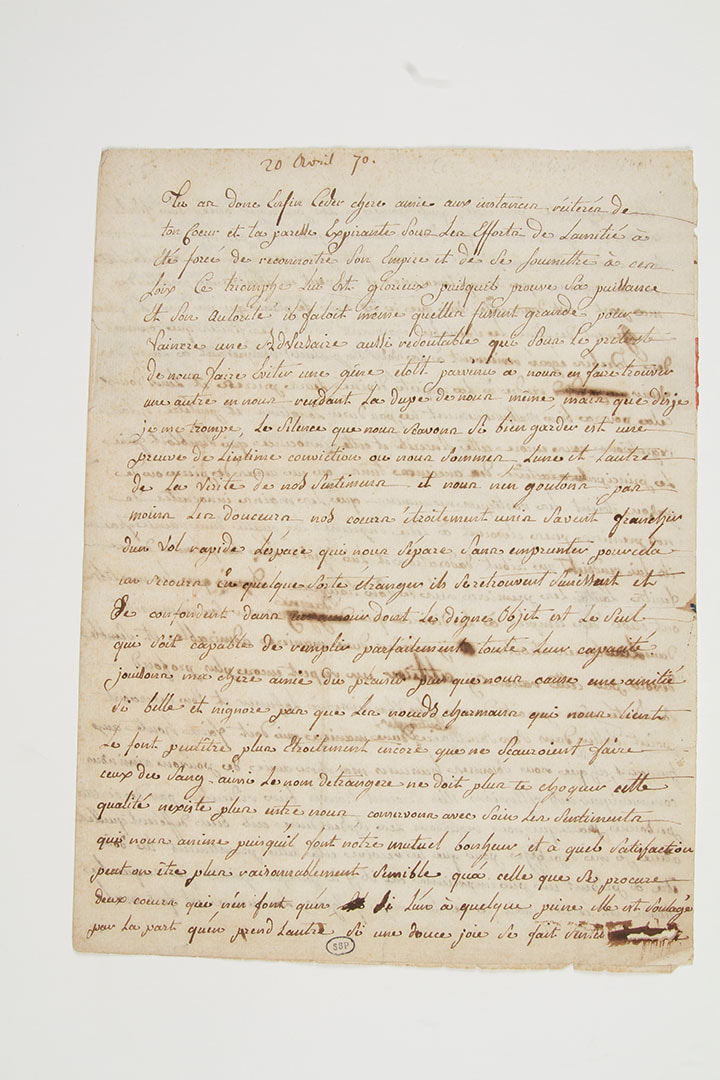

In August 1782, Manon was in Amiens, while her husband, travelling for business, was in Paris. Jean-Marie Roland was inspector of Commerce and Manufactures, had his office in Amiens. The couple lived there for the first four years of their marriage (1780-1784) and their daughter was born there in October 1781. Most of the time, the couples were working on an Encyclopedia of textile manufacture, gathering expert articles, researching and writing, and editing. When Jean-Marie was promoted to general inspector, the family moved to Lyon, and Manon was able to live in the family's nearby country home, Le Clos. Whenever they were apart, the couple corresponded. On 8 August 1782, Manon wrote to Jean-Marie: I hear, my friend, from M.d'Antic, that you are arrived, and while at first I only meant to let you know through him how pleased I was, I thought that at the same time I should pass on to you the included, which is from Villefranche where you must reply. It came together with a piece for Despreaux, from the lawyer Dessertines who disserts on Greek chronlogy as an ex-jesuit. (Please don't tell the chanoine this is from me, as it talks about the Deluge, and Moses, etc, things and people I don't wish others to think I have fallen out with). Monsieur d'Antic was Bosc d'Antic, who, after 1789, went only by Bosc. He was a close friend of the Rolands, a botanist who helped them in the botanical part of their Encyclopedia. The 'chanoine' was Roland's brother, a religious man. Both Manon and Jean-Marie were atheists, but Manon liked her brother in law very much and did not wish to argue with him too loudly. As to the young lady, the editor of the letters refers to Manon's childhood friend and correspondent, Sophie Cannet, who introduced her to her husband. Sophie was considering an offer of marriage from a much older man. She eventually gave in, and a few years later was a widow with two children. Letter from Manon Phlipon (Roland) to Sophie Cannet in 1770. (Lot 33o Bilbliorare)

0 Comments

Although she was born and bred in Paris, Manon Roland spent the first three years of the Revolution in Lyon at her husband's country home of Le Clos, living a simple, retired life. There she received visitors who played an important role in the revolution and corresponded with others, notably Brissot, who printed several of her letters in his paper Le Patriote François. Madame Roland prided herself on fully taking part of the country life, picking grapes during the vendanges, and mixing with her peasant neighbors on equal and easy terms (or so she thought, anyway). In July 1789, within six days of the fall of the Bastille, a rumor spread through France that brigands, or perhaps the English, were sacking the country. People everywhere panicked, and soon, the peasants who'd armed themselves to fight this fictitious enemy began to revolt, sometimes violently, setting fire to the homes of the rich and murdering their inhabitants. People were advised to leave the countryside and come to Paris, where they would be safer. Madame Roland responded in a letter published anonymously by Brissot: Every one tells me to move to the city—I will not. I have not hurt any body in the country, I have no land nor title, I have only done good to my neighbors. Were they to become ungrateful, so what? I will pay the interest of the advantages that my position gave me over them. But I will not do them the injury of believing it before the event, and even if I were to fall victim to a few bandits, I would not despair of the res publica, as do the cowards who call for a counter-revolution because a few houses were burnt down. The Rolands eventually did come up to Paris in 1791, not out of fear, but because they wanted to participate in the political events that were taking place in the Capital. Unfortunately, this did little to increase their safety as they both died in 1793.

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed