|

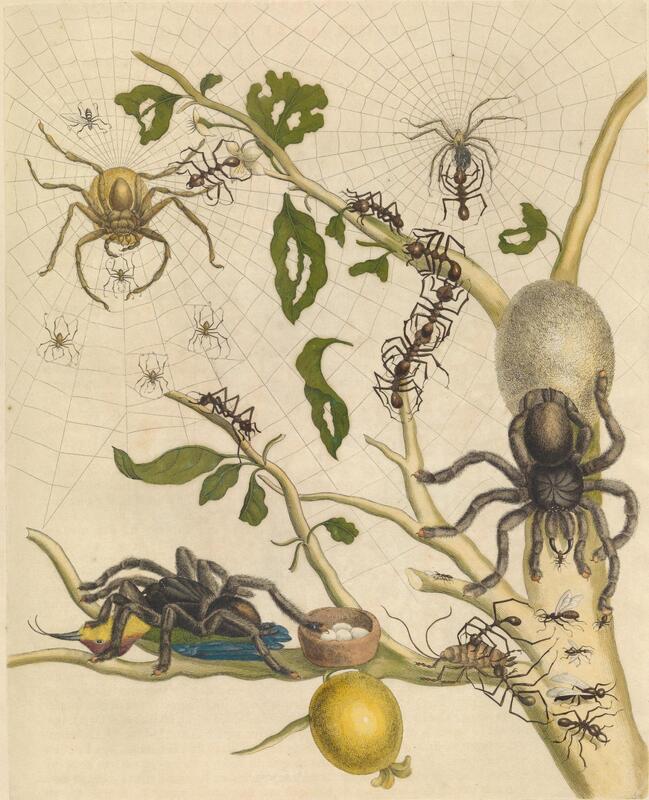

As any woman who has come across, well, men, knows, sexism is very often justified by spurious appeals to science, whether it is biology, evolutionary theory, brain science, or in a more puzzling twist, mathematics ('It's maths, deal with it!' says random man on twitter). So it might be fun to know that, in the late 18thcentury, one woman sought to debunk sexism with an appeal to the study of the natural world. Here are Olympe's words from The Rights of Woman: Reconsider animals, consult the elements, study plants, finally, cast an eye over all the variations of all living organisms; yield to the evidence that I have given you: search, excavate and discover, if you can, sexual characteristics in the workings of nature: everywhere you will find them intermingled, everywhere cooperating harmoniously within this immortal masterpiece. This is perhaps not entirely accurate, but it's quite a lot better than the pseudo science that is continuously peddled at us via social media! My one criticism is that she might have reminded her readership of a number of species that don't quite fit that model of collaboration between the sexes. I'm thinking of the spider and the praying mantis.

0 Comments

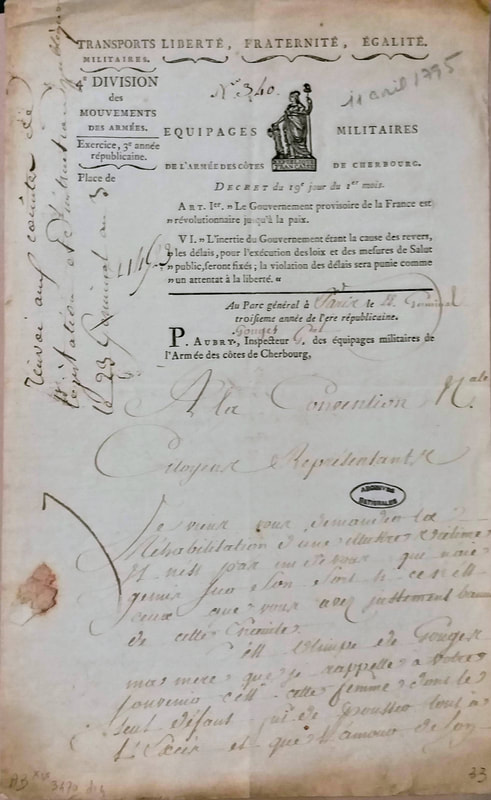

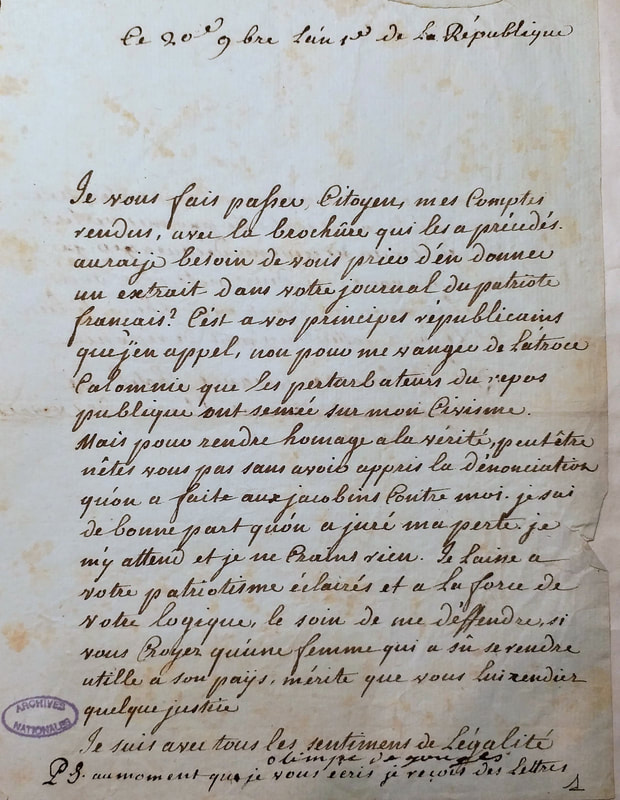

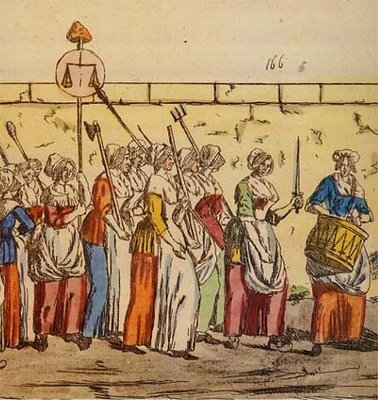

Olympe de Gouges is famous for having claimed that 'marriage is the tomb of love'. And as happened with Mary Wollstonecraft, she runs the risk of being read as a defender of free love, scornful of monogamous unions. This, however, misunderstands her position, which is a criticism of certain social manifestations of marriage, which run deeper than just a comment on love and unions, and addresses the reduced capacity of humans for co-operation as they learn to believe in the superiority of reason and science over everything else. Reconsider animals, consult the elements, study plants, finally, cast an eye over all the variations of all living organisms; yield to the evidence that I have given you: search, excavate and discover, if you can, sexual characteristics in the workings of nature: everywhere you will find them intermingled, everywhere cooperating harmoniously within this immortal masterpiece. Olympe is not simply criticizing men's capacity to see women as ally they ought to co-operate with, but as missing the point of co-operation generally, because they are 'puffed up with science'. She is, it seems, criticizing the rise of individualism, of the belief that reason alone is our master, and that only men have that. This is borne out in her discussion, in Le Bonheur Primitif, of how an individual's need for glory puts a stop to a well functioning, happy community of men and women. And a key factor in this happiness is marital union: For man's happiness, and for natural law, the finest institution was the respect they felt for the sacred ties that united spouses; two beings were only bound together according to their reciprocal feelings. But when the social cohesion is broken, marriage is no longer the key to happiness, quite the contrary: Marriage is the tomb of trust and love. A married woman can, with impunity, give bastards to her husband and a fortune that is not theirs. The unmarried woman only has the feeblest rights; ancient and inhuman laws forbid her the right to the name or wealth of the father of her children and no new laws have been devised to address this matter. Pierre Aubry was the son of Olympe de Gouges and the man she was forced to marry as a teenager. He was born in 1766, a year after his parents were married. In 1767, his father either died or disappeared, and Olympe became solely responsible for his upbringing. As a single mother, Olympe de Gouges did everything she could to ensure that her son received the good education she did not have, paying for tutors to make up for the fact that she could not teach him herself. She also included him in her own life, and as a child he became part of her theatrical group. When he was old enough, she bought him a place in the army. Given this, what happened after her death seems like the lowest possible treason. Five days after his mother's death, Aubry published an 'Address to the public' in which he recused his mother and all her work. Yes, this was not the end of the story. In a letter written on 11 April 1795, a year and a half after his mother's death, Pierre Aubry wrote to the National Convention to ask that Olympe de Gouges's name be rehabilitated. I am writing to ask you to rehabilitate an illustrious victim. On 20thNovember 1792, Olympe de Gouges wrote to Jacques Pierre Brissot, editor of Le Patriote Francais, sending him a set of documents and asking that he should extract them in his paper. She had been denounced at the Jacobins club and feared for her safety. In the PS, she says that she has also received threatening letters and would like to set up a meeting with Brissot to discuss her situation. Gouges had in fact been denounced at the Jacobins by Leonard Bourdon, for having written against the Jacobins's actions leading to the massacres of 10 August and 2 September 1792. The Jacobins, she claimed, especially Marat and Robespierre, were entirely responsible for inciting popular violence. Interestingly, Manon Roland had blamed Danton for the same thing. But from inside the Government, Manon knew, or suspected, that it was Danton who'd ordered the signal to start the massacre, while Olympe, as a public writer and philosopher, knew that it was the speeches and writings of Marat and Robespierre that had prepared the people to react to that signal. The two documents that Olympe sent Brissot can be found on Clarissa Palmer's excellent site : Court correspondence. A principled report and my last words to my dear friends, by Olympe Degouges [sic], to the National Convention and to the People. On a denunciation made to the Jacobins, against her patriotism, by Monsieur Bourdon Prognostic of Maximilien Robespierre, by an Amphibious Animal published 5 November 1792, in which she attacks Robespierre and Marat for inciting the people to violence on August 10 and September 2. Below is a translation of the letter to Brissot and a photograph of the actual letter taken at the Archives Nationale on 5 June 2019 (446AP/7-18) Note that the letter and the signature are in different hands, as Gouges was using a secretary. Note also that she signs herself 'Olimpe', not 'Olympe'. 20 November, year 1 of the Republic In 1788, when he first presented his ‘What is the third estate’, the Abbé Sieyès declared that : “inequalities of sex, size, age, colour, etc. do not in any way denature civic equality” (Sieyes, Political Writings, 155). These, he said, like inequality of property, are incidental differences and cannot affect civic rights. But Sieyès, it turns out, was not so committed to equality, however, that he wanted to extend rights active citizenship to women. In his Préliminaire de la Constitution, written on 22 July 1789, he writes: All of a country’s inhabitants must enjoy the rights of passive citizenship: all have the right to the protection of their person, their property, their freedom, etc. But not all have the right to take an active part in the formation of public powers, all are not active citizens. Women, at least in the current state of things, children, foreigners, those that contribute nothing to supporting the public establishment must not actively influence the republic. Women did not remain silent. Then journal editor, Louise Keralio, responded four weeks later: We don’t understand what [Sieyès] means when he says that not all citizens can take an active part in the formation of the active powers of the government, that women and children have no active influence on the polity. Certainly, women and children are not employed. But is this the only way of actively influencing the polity? The discourses, the sentiments, the principles engraved on the souls of children from their earliest youth, which it is women’s lot to take care of, the influence which they transmit, in society, among their servants, their retainers, are these indifferent to the fatherland?... Oh! At such a time, let us avoid reducing anyone, no matter who they are, to a humiliating uselessness. Keralio is clearly angered by Sieyès’ formulation: in what sense are women not active, she asks? What is there of passivity in the work they conduct from the home, nurturing republican values and giving birth to new citizens? Like Manon Roland, she was a reader of Rousseau, and was convinced that there was a place for women in Republic that was central to the flourishing of the nation, even though that place was in the home rather than in the assembly. So she does not disagree with Sieyes that women should stay home, rather than participate in debates taking place in public fora, but she believes that the home is just as important a place for the making and cultivating of the republic than the assembly. Olympe de Gouges’s famous response was printed at the same time as Louis XVI ratified the constitution drafted by Sieyès, in September 1791. Man,” she asks “are you capable of being fair? A woman is asking: at least you will allow her that right. Tell me? What gave you the sovereign right to oppress my sex? Your strength? Your talents? Observe the creator in his wisdom, examine nature in all its grandeur for you seem to wish to get closer to it, and give me, if you dare, a pattern for this tyrannical power. On behalf of women in general, she expresses her outrage that women have been exclude from active participation in the city, with no argument, other than that they belonged to the class of those who ‘contribute nothing to supporting the public establishment’. Women, she knows, contributed both physically – by fetching the royal family from Versailles – intellectually – by debating new ideas in circles and political societies, publishing pamphlets proposing reforms (such as her proposal for a voluntary tax) – and materially – by giving money and jewels to relieve poverty and help pay off the national debt. Unlike Louise Keralio, she does not even feel that she needs to appeal to women’s contribution to the republic quamothers. Yet, she does not hesitate to remind the public that women are also mothers: Mothers, daughters, sisters, representatives of the Nation, all demand to be constituted into a national assembly. Given that ignorance, disregard or the disdain of the rights of woman are the only causes of public misfortune and the corruption of governments [they] have decided to make known in a solemn declaration the natural, inalienable and sacred rights of woman; this declaration, constantly in the thoughts of all members of society, will ceaselessly remind them of their rights and responsibilities, allowing the political acts of women, and those of men, to be compared in all respects to the aims of political institutions, which will become increasingly respected, so that the demands of female citizens, henceforth based on simple and incontestable principles, will always seek to maintain the constitution, good morals and the happiness of all. The following is translated from the description of an exhibition of Korean artist Nam June Paik (1932-2006) at the Grand Palais in Paris, in June-July 2018. "Olympe de Gouges (1989) – writer, feminist pioneer and anti-slavery activist, executed in 1793 – is a robot made out of twelve CTR colour televisions inserted in a frame made out of twelve wooden ancient tvs. The work itself is on laser VD. On the sides are painted chinese characters meaning “French woman, Truth, Goodness, Beauty, Liberty, Passion” refering to the wording of the commission to the artist by the City of Paris for the celebrations of the bicentenial of the French Revolution in 1789."

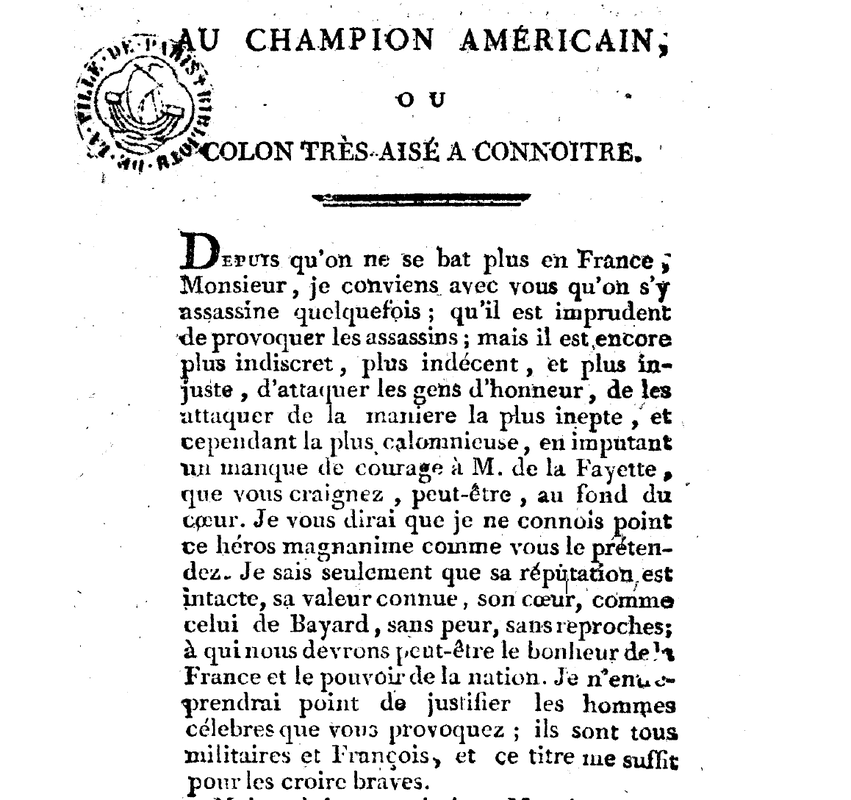

In 1783 Olympe wrote her first play, Zamore et Mirza, ou l’heureux naufrage, and submitted to the Comédie Française. The actors liked it and accepted it. Unfortunately, her later dispute with Beaumarchais over Le Marriage Innatendu de Chérubin, meant that the Comédie just sat on her play and refused to put it on. The contract she had signed with them meant that it could not be played elsewhere in Paris. So Olympe took the play elsewhere, with her own theatrical troup, which included her son, and performed it in private theatres and in the provinces. In 1786, she had the play printed for the fist time. Two years later, she printed it again, with a postface, her “Réflections sur les hommes nègres” in which she explained what the philosophy behind the play was. Why are black people treated like animals, she asked? [I] clearly observed that it was force and prejudice that had condemned them to this horrible slavery, that Nature had no part in it and that the unjust and powerful interest of the Whites was responsible for it all. In 1788, Olympe was already sensing a change for the better in politics, and felt it her duties to show the world that if they wanted to redress injustice, slavery was the place to start: When will work be undertaken to change it, or at least to temper it? I know nothing of Governments' Politics, but they are fair, and never has Natural Law been more in evidence. They cast a benevolent eye on all the worst abuses. Man everywhere is equal. As she pointed out in January 1790, in an open letter to an (anonymous) American colonist attacking her play, at the time she wrote Zamore and Mirza, there was no organised French abolitionist movement. The Societé des Amis des Noirs did not yet exist. She ponders in that letter, whether it was her play that caused Brissot and the others to create that society, or whether it was just a happy coincidence: I can therefore assure you, Sir, that the Friends of the Blacks did not exist when I conceived of this subject, and you should rather suppose that it is perhaps because of my drama that this society was formed, or that I had the happy honour of coincidence with it. In fact, Brissot did take note of the play, and in the winter 1789, he made use of his growing influence to persuade the actors of the Comédie Française, finally to put it on. Unfortunately, the actors bore a grudge, so they arranged for the play to be put on on the last day of the year, after which Parisians would be returning to their family homes to celebrate the New Year. The contract required that a play make a certain amount of money in the first three days if it was to stay on the program. The first night was a success – but a political rather than an artistic one. People came to support it and to protest against it, and they were so loud about it, that few could hear the actors. Fortunately the text was in print, and reviewers at the time noted that they’d had to refer to the printed version to know how the play ended. Those who protested against the play most vociferously were the colonists, who had strong financial interest in the laws regarding slavery staying as they were. One such colonist wrote to Gouges, imputing that she was but the tool of Brissot’s society, and that her play was a call for the slaves of America to revolt. Gouges responded in an open letter, (1790) arguing, as we saw, that it was she, not Brissot, who’d first given voice to the abolitionist in France, and that her play did not incite revolution, but that it enjoined the French people and the colonists to see that all men were equal and abolish slavery, and the slaves to trust in the new laws and wait for a better future. Two years later, these accusations came back when the slaves and the free people of colour of Saint-Domingue revolted. Not many in the eighteenth century agreed that women should be writers of anything other than gossipy letters. But even those who did found it hard to agree as to when was the best time for a woman to become a writer. A woman who had the misfortune not to be married or have children could write at any time, provided she did not disturb her relatives. Hence Jane Austen would get up early, before her family’s breakfast, and write at the dining table. Afterwards there was household tasks to attend to, of course, and any other time she could take up a pen was devoted to writing letters to family members who were away. Considerations of respectability only applied to respectable women, of course. So Olympe de Gouges, widowed, living under her assumed name instead of her husbands (Aubry), bringing up her boy alone, assisted financially by her lover, and pursuing a career as a playwright could write when she wanted to. This is probably why her biographer lists over 140 pieces penned by Olympe in the last five years of her life. (Her writing career began 1788 and she died in 1793) Little is known of Sophie de Grouchy’s writing habits, except for a report from her aunt that as a twenty year old, staying in a convent finishing school in Normandy, she spent so much time reading and translating that she made herself ill and damaged her eyesight. Given that the social life of the school was quite active – the idea was for the young women to be presented to society and hopefully find husbands – Sophie probably worked during the night, by candlelight. The only obstacle standing between her and her work then was her social life, and it is likely that even when she married and became a mother this carried on, i.e. that her activities as a saloniere were the only thing that stopped her from writing when she wanted to. Her daughter, Eliza, had a wetnurse, so that Sophie was not bound by the usual duties of motherhood. Manon Roland was firmly opposed to wet-nursing, being a follower of Rousseau, and a middle class woman, less able to ‘adopt’ a nurse, i.e. invite a woman to become a permanent member of the family and live under their roof until she could be retired. Manon also had some duties at home. Even though she had servants, they had to be trained, supervised, their work had to be done for them when they were sick and big jobs, such as laundry, had to be shared, and dinner had to be ordered, and prepared by herself when she wanted something done in a particular manner. And most importantly, children – in her case a daughter, Eudora – had to be educated following Rousseauian precepts. But none of this, Manon reflected, ought to take particularly long, so that a good mother and housewife ought still to have plenty of time for study and writing. Those who know how to organize their work always have leisure time. It is those that do nothing that lack the time to do anything. Moreover it is not surprising that women who spend their time in useless visiting and who think they are badly dressed if they have not spent a great deal of time at their mirror, find their days too long through boredom and too short for their duties. But I have seen those we call good housewives become unbearable to the world and even their husbands through a tiresome attention to little things. Manon’s stance was not unlike that of Mary Wollstonecraft, who claimed that a married middle class woman with children was in an ideal position, once her children were at school and no longer needed her full time attention, to take up science, literature or the arts. And did they pursue a plan of conduct, and not waste their times in following the fashionable vagaries of dress, the management of their household and children need not shut them out from literature, nor prevent their attaching themselves to a science, with that steady eye which strengthens the mind, or practicing one of the fine arts that cultivate the taste (VRW). Both in Roland and Wollstonecraft’s case, however, the life plan that would allow women to write while mothering young children relied very much on a reformed, republican and proto-feminist model of family life in which only necessary household duties were perfomed - the ‘vagaries of dress’ to be avoided and ‘if men do not neglect the duties of husbands and fathers’. I expect a woman to keep her family’s linen and clothing in good order, to feed her children, order, or herself cook dinner, this without talking about it, keeping her mind free and ordering her time so that she is able to talk of something else, and to please, at last, through her mood, as well as the charms of her sex So what would an 18th woman who wanted to write but had no expectations that a revolution would bring about major changes in her household duties do? This was the case of Hannah Mather Crocker, born in Boston in 1752, writer of several books and pamphlets, including “Observations on the Real Rights of Women” a work in which she cites Wollstonecraft amongst others. Crocker, although she had always been philosophically inclined, only began to write in earnest once her ten children had left home, remarking that this period in a woman’s life was : a fully ripe season to read, write, meditate and compose, if the body and mind are not enfeebled by infirmities. In other words, if bringing up ten children hasn’t left you a mental and physical wreck, now is the time to pursue a literary or philosophical career!

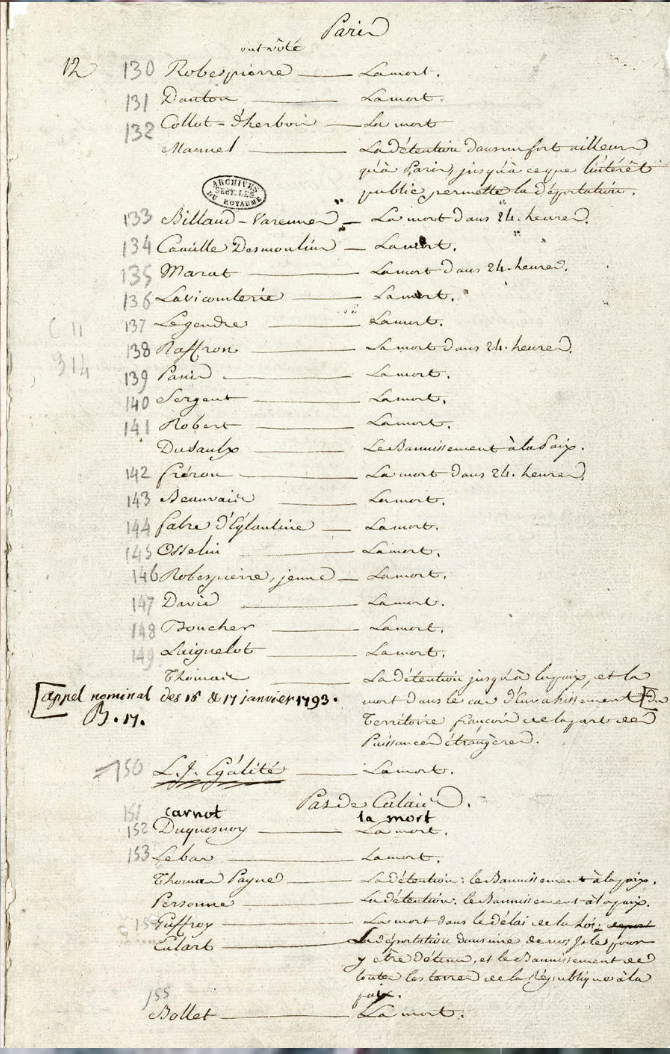

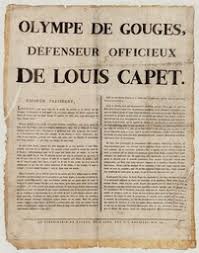

On 15 January 1793, Louis Capet, previously King of France, is found guilty by an overwhelming majority of the 749 deputies. Two days later, the deputies are asked to vote for a penalty. 346 vote for the death penalty. Others, including Thomas Paine, who had been offered honorary French citizenship, vote for exile, or for imprisonement. . One citizen, who had not voted, argued against the death penalty. Olympe de Gouges started by offering herself as Louis’s unofficial advocate on 16 December, arguing at first that while as a King, he had done harm to the people of France by his very existence, once Royalty had been abolished, he was no longer guilty. As king, I believe Louis to be in the wrong, but take away this proscribed title and he ceases to be guilty, in the eyes of the republic. This proposal, written as a letter to the Convention, was then printed as a placard and distributed throughout Paris. The Convention disregarded the letter. Sèze was made Louis’ advocate, and the argument that Gouges put forward was not taken into consideraton. Louis Capet, stripped of his title, was still tried for high treason, i.e. for actions he had performed while he was still King of France. Olympe did not stop at this. On 18 January, after the King had been found guilty, but before his death had been voted, she put up another placard addressed to the Convention and to the people of Paris, entitled “Decree of Death against Louis Capet, presented by Olympe de Gouges.” In this piece she also attempted to dispel the mistaken impression that she was in fact a royalist. Louis dead will still enslave the Universe. Louis alive will break the chains of the Universe by smashing the sceptres of his equals. If they resist? Well! Let a noble despair immortalize us. It has been said, with reason, that our situation is neither like that of the English nor the Romans. I have a great example to offer posterity; here it is: Louis' son is innocent, but he could be a pretender to the crown and I would like to deny him all pretension. Therefore I would like Louis, his wife, his children and all his family to be chained in a carriage and driven into the heart of our armies, between the enemy fire and our own artillery. (http://www.olympedegouges.eu/decree_of_death.php) Here Gouges is appealing to a well-known fact about the workings of royalism: a King cannot die. The holder of the title may die, but the title passes automatically to the next contender, without, even, the necessity of sacrament. The immortality of the king was such an important precept that a Chancelier, when a monarch died, could not wear mourning. Bossuet captured the phenomenon thus in his Mirror for Kings: Letting Louis live, she would go on to argue in her final published piece, 'Les trois urnes'. would have made it clear that he was no longer a threat to the republic - as no one individual is. To execute him is both to betray a certain lack of confidence in whether the people have truly succeeded in aboloshing the monarchy, and perpetuate that doubt, as after Louis's death, his title is transferred to his descendent.

On 7 November 2017, 314 Francophone teachers signed and published a document promising not to teach or enforce a particular rule of French grammar:

"Le masculin l'emporte sur le féminin" - that is, when a noun group is of mixed gender, the corresponding pronouns and adjectives should be written in the masculine form, because that form is 'stronger' or 'wins over' the feminine one. For instance, a group of men reading is refered to as 'lecteurs', a group of women reading as 'lectrices' but a mixed group as 'lecteurs'. Proponents of Inclusive Writing suggest that it should be 'lecteur·rice·s' The guardians of the French language, the Academicians, who are in charge of vetting new dictionary entries and proposals for grammatical reform, immediately rose against the proposal, declaring it to constitute a 'mortal danger' for the French language'. The minister of education, Jean-Michel Blanquer, agreed, adding that it was 'very ugly' and that real feminists should concern themselves with other, more important problems. The Prime Minister Edouard Philippe followed suite, declaring that the new 'écriture inclusive' would not be legal in official documents. Two years before the petition for inclusive writing was signed, historian Eliane Viennot addressed the National Assembly on the need to reform language. She has since been an active member of the movement and noted that far from being new, the idea that language should be reformed to include women as equals dates back, in France, to the Revolution, and in particular to Olympe de Gouges. According to Viennot, Gouges's Declaration of the Rights of Woman was a direct challenge to the failure to include women in the new Constitution. Viennot points out that 'l'homme' in French does not, and never did correspond to 'humanity', but really only to male humanity. Counting the number of uses of the word in several authors of the Enlightenment, she says it is clear that the word is not meant to include women, except on a few occasions. Pretending that the use of the masculine is neutral or universal is pure hypocrisy - except if we understand 'universal to mean 'applying to men only' which in the French 'universal suffrage' of 1848 , it did. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed