|

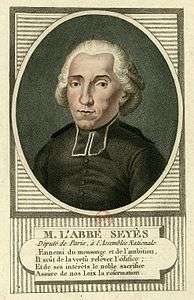

Equality is not often discussed in a republican context, as liberty is more central to that debate. But equality also plays a role in 18thcentury republicanism ‘Liberty, Equality’ was the first motto of the French Revolution. Republican liberty is all about non-domination: living under a despot, a king, is being dominated even when the King is not intentionally harmful. The very fact that one person is in a position to interfere with the lives of all on a whim is tyranny, and results in the absence of freedom. Republican equality is also defined in contrast to tyranny. It is equality of status in relation to the law that prevents one individual from being dominated by another. This was framed early on in the Revolution by Abbe Seiyes in “What is the Third Estate”: I picture the law at the center of an immense globe. All citizens without exception are at the same distance from it on the surface and occupy equal space. All equally depend on the law; all give it their liberty and property for protection. This is what I call the citizens’ common right, whereby all are alike. [...] If [...] one person comes to dominate his neighbour, or to usurp his property, the common law will repress his attempt. Emmanuel Joseph Sieyes (1748-1836), pictured with and without his religious garb. Equality of status must have seemed especially urgent for the women involved in the Revolution, as they must have understood that without that, they could not claim the freedom that was on offer as they would remain under the domination of their husbands. And in 1788, it looked as though they would benefit from the title of citizen and therefore receive equal status. Sieyes, when asked who would count as equal replied that “inequalities of sex, size, age, colour, etc. do not in any way denature civic equality”. These, he said, like inequality of property, are incidental differences and cannot affect civic rights. One good place to start in establishing republican equality, one place where it was very clearly wanting, was the criminal law. Sieyes called the use of privilege in punishment an ‘abominable distinction’: Why do the privileged, when they commit the most horrible crimes, nearly always escape punishment, thereby stealing from the public potentially most effective examples? [...] The law dictates different sentences for the Privileged and he who is not. She seems to follow the Noble criminal with its tenderness, and to want to honour him even at the scaffold. Two years after Sieyes wrote ‘What is the Third Estate’, and when it became clear that sex would make count towards equality after all, Olympe de Gouges argued, along similar lines, that for women to have equal status as citizens would mean in the first instance, equal status in the face of criminal law: VII. No woman may be exempt; she must be accused, arrested and imprisoned according to the law. Women, like men, will obey this rigorous law.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed