|

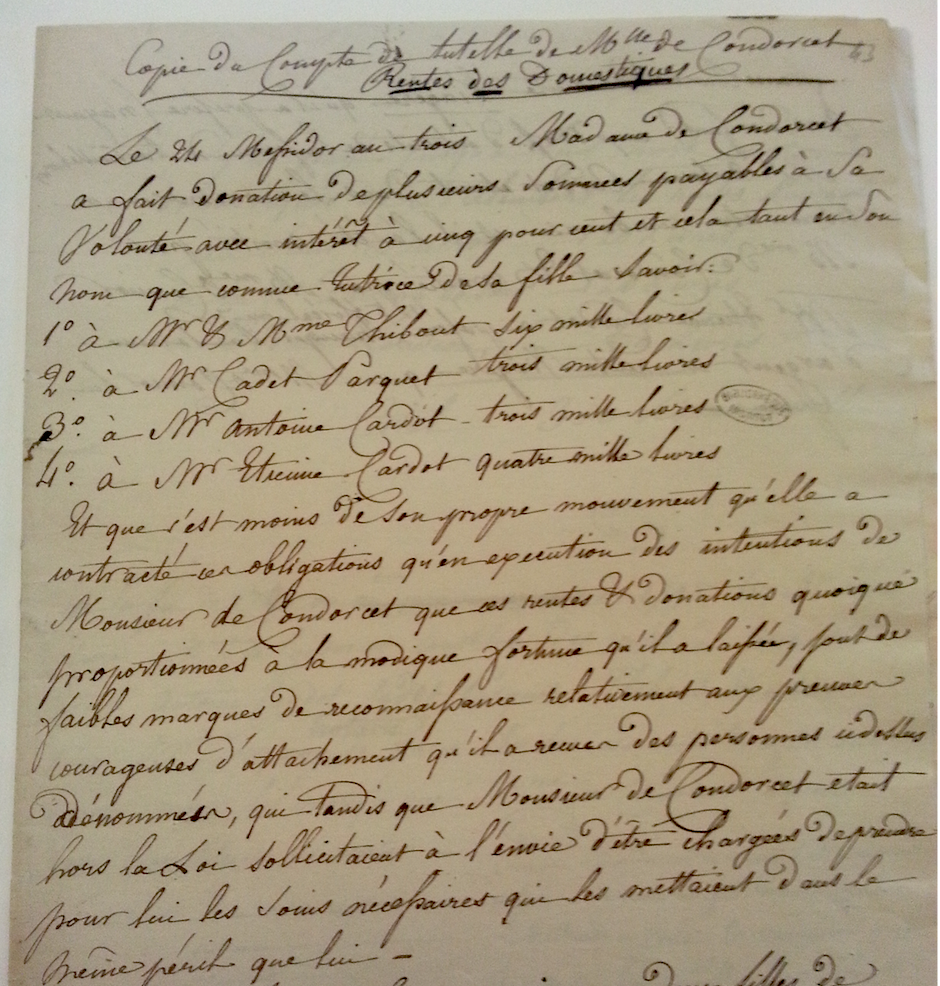

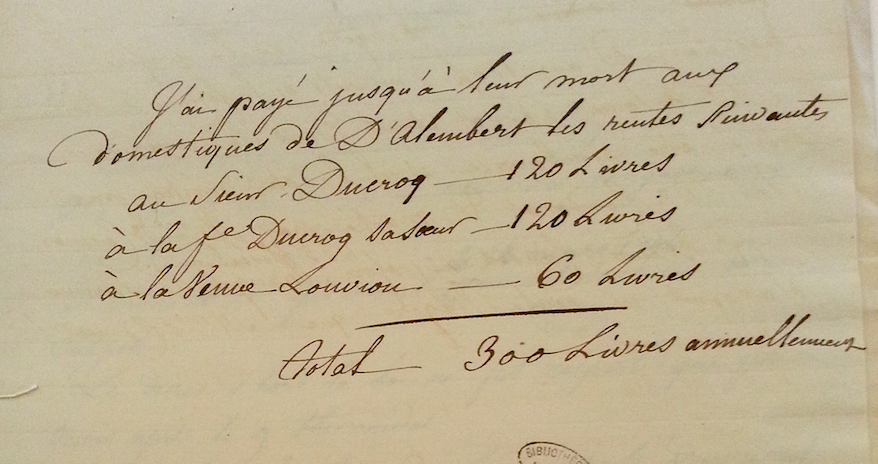

In Sense and Sensibility, one of Austen’s least likable characters, Fanny Dashwood, explains to her husband why she feels it would be a bad idea to offer his fathers’ widown and his three half sisters a modest annuity of 100 pounds: People always live for ever when there is an annuity to be paid them; and she is very stout and healthy, and hardly forty. An annuity is a very serious business; it comes over and over every year, and there is no getting rid of it. You are not aware of what you are doing. I have known a great deal of the trouble of annuities; for my mother was clogged with the payment of three to old superannuated servants by my father's will, and it is amazing how disagreeable she found it. Twice every year these annuities were to be paid; and then there was the trouble of getting it to them; and then one of them was said to have died, and afterwards it turned out to be no such thing. My mother was quite sick of it. Thankfully for the family, one of the daughters marries a rich man, and there is, at the end of the story, no prospect of them starving. But annuities were the rather arbitrary mean whereby widows and spinsters lived, and this was also true of those who had been in service, and retired, or lost their place through their master’s death. The continuation of these people who were in control of a sufficient sum was wholly dependent on the good will of a rich relative, whether of their own or of their employer. Sophie de Grouchy was no Fanny Dashwood. She cared for her old nurse all her life. She paid her an annuity, but also lived with her and cared for her when she was sick. When Condorcet died, Sophie, in charge of managing his (small) assets on behalf of their daughter took on his obligations. She paid sums of money to Condorcet’s old servants, M and Mme Thibaud, and M Parquet, to his secretary, Cardot, and his secretary’s brother. She records that she took on these obligations because she knew that this had been Condorcet’s intention. She adjusted the payment according to the needs of the payees – the Thibauds asked for an annuity to be paid to their daughters, Parquet and Cardot chose a life annuity for themselves and Cardot’s brother a single sum, which he could put towards his commercial entreprise. Sophie also notes that she carried on paying the annuities of D’Alembert’s servants until their death. D’Alembert had been Condorcet’s close friend so she felt obligated towards them.

0 Comments

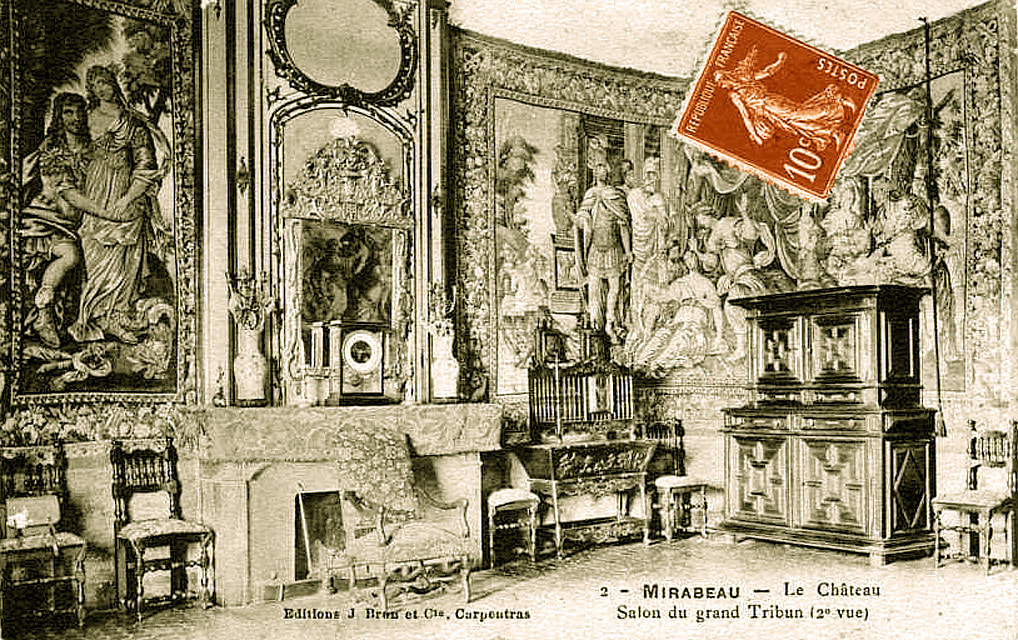

If Sophie de Grouchy struggled financially during the Terror, and in the years following it, because hers and Condorcet's wealth had been confiscated, she clearly did not stay poor long. In 1805, she purchased her castle for her 15 year old daughter, Eliza. The castle, Bignon-Mirabeau, is in the Loiret, an hour and a half's drive from Paris with no traffic, but a more substantial journey in a horse-drawn carriage. The castle was named after its previous owner's family: the Marquis de Mirabeau had been born there, and had sold it in 1789, shortly before he died. Owning a castle during the revolution was no easy feat. Its first buyer abandoned it and run away to England. Its second one had it less than ten years. . Two years after she received the castle as a gift, Eliza married an Irish man, the son of a friend of her parents, Arthur O'Connor. The castle stayed in the family, which, over the generation acquired the family name La Tour du Pin. It can be visited today, and among the exhibits, one can see a collection of mementos of Sophie de Grouchy's life, including a self-portrait miniature.

For more information on the castle, see here. . It is highly unlikely that Sophie, Olympe or Manon ever did take a holiday by the sea. And if they did, they would not have done so together, Nonetheless I will ask you to stretch your imagination and picture them together, in Dieppe (the first French seaside resort), in the summer of 1791. Their children would be there too – Manon’s Eudora, just turned ten, Sophie’s Eliza, five, and Olympe’s adult son, Pierre Aubry with his wife. And then let's leave them there together, dipping their toes in the water and relaxing before going back to face the Terror. This is also what I'll be doing for the next two weeks - relaxing, and hopefully not facing the Terror - and won't be posting until I get back at the end of July. Have a great summer!

Letter to Sophie Cannet, 5 July 1776.

Twenty-two year old Manon's letter to her convent friend, Sophie, is very reminiscent of Seneca's Letters to Lucilius. And just like him, she believes that although the Stoic sage must be self-sufficient, that is no reason not to value friendship.

Of course she did not know then that her capacity for self-sufficiency would be tested - and found to be quite strong - during the long weeks she spent in prison, awaiting death. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed