|

Olympe de Gouges is famous for having claimed that 'marriage is the tomb of love'. And as happened with Mary Wollstonecraft, she runs the risk of being read as a defender of free love, scornful of monogamous unions. This, however, misunderstands her position, which is a criticism of certain social manifestations of marriage, which run deeper than just a comment on love and unions, and addresses the reduced capacity of humans for co-operation as they learn to believe in the superiority of reason and science over everything else. Reconsider animals, consult the elements, study plants, finally, cast an eye over all the variations of all living organisms; yield to the evidence that I have given you: search, excavate and discover, if you can, sexual characteristics in the workings of nature: everywhere you will find them intermingled, everywhere cooperating harmoniously within this immortal masterpiece. Olympe is not simply criticizing men's capacity to see women as ally they ought to co-operate with, but as missing the point of co-operation generally, because they are 'puffed up with science'. She is, it seems, criticizing the rise of individualism, of the belief that reason alone is our master, and that only men have that. This is borne out in her discussion, in Le Bonheur Primitif, of how an individual's need for glory puts a stop to a well functioning, happy community of men and women. And a key factor in this happiness is marital union: For man's happiness, and for natural law, the finest institution was the respect they felt for the sacred ties that united spouses; two beings were only bound together according to their reciprocal feelings. But when the social cohesion is broken, marriage is no longer the key to happiness, quite the contrary: Marriage is the tomb of trust and love. A married woman can, with impunity, give bastards to her husband and a fortune that is not theirs. The unmarried woman only has the feeblest rights; ancient and inhuman laws forbid her the right to the name or wealth of the father of her children and no new laws have been devised to address this matter.

1 Comment

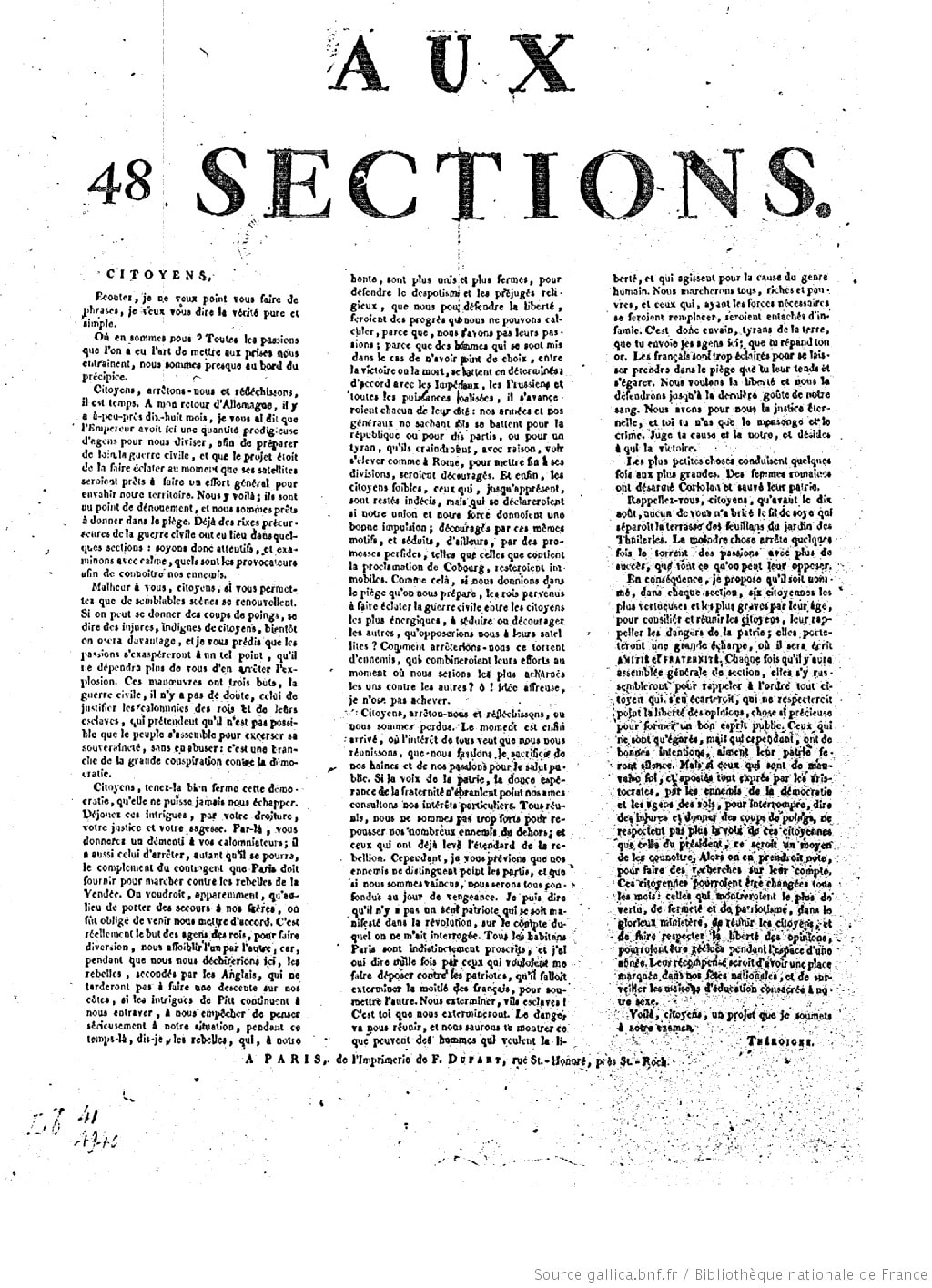

Anne-Josèphe Terwagne was born in Mercourt, in Belgium in 1762. As a child and a young woman, she was abandoned, moved from house to house, country to country, job to job, and eventually ended up in Paris, with some money left her by a lover. There she took up the name Théroigne de Méricourt and started to dress in Amazon fashion, that is a comfortable style of dress that allows women the same freedom of movement as men She was an early enthusiast of the French Revolution who spoke out in favour of women's rights, but especially of women's participation, demanding that she be allowed to arm a battalion of women, so that if the men had to leave France to fight abroad, the country would not be undefended. In 1790, during a trip back home in Belgium, she was arrested and taken to an Austrian prison, where she was interrogated about her revolutionary activities. The text below was written shortly after her return. It is an address to the 48 'sections' of Paris, the units of democratic government that had replaced the 'districts' set up in 1789. During her imprisonment, Theroigne learnt much about what foreign powers intended for France. What the enemy wants is division among the French, Civil war. She cites the fact that there has been some in-fighting in Paris already, and explains that the foreign enemy does not care about party politics except in so far as it sets the revolutionaries against each other. "Citizens" she says. "Let's stop and think, or else we are lost." If we care about the public interest, she carries on, we must put aside our personal differences and band together. The French, she says, are enlightened, and they will fight for their liberty till the last drop of blood. It wouldn't take much, she adds, to put a stop to the in-fighting and change the course of the revolution back to its true goals. After all, she says, it didn't take much for the French to step over the line and massacre the King's army at the Tuileries the previous year.  So here's what she suggested: "I propose, consequently, that each section should elect six older female citizens amongst the most virtuous and wise to reconcile and unite citizens and remind them of the dangers faced by their country. They will wear a large scarf on which it will be written 'FRIENDSHIP' and 'FRATERNITY'. Whenever the section hold a general assembly, they will be present in order to call to order any citizen who would stray, and would not respect the freedom of opinion, so precious for the creation of a good public spirit. Those who have only strayed but have good intentions and otherwise love their nation will keep silent. But those of bad faith, placed here by the aristocrats, the enemies of France and the agents of the king to interrupt, swear, and fight will not listen to the voice of those female citizens any more than to that of the president so it will be a way of finding out who they are. Their names will be noted and they will be investigated. Those female citizens should be changed every six months. Those that demonstrate the most virtue and firmness in their task of uniting citizens and protecting freedom of opinion can be re-elected within one year. Their reward should be to have a special place in our national holiday, and to be in charge of inspecting the schools for girls. As I find myself single parenting my son for a whole 12 days, I feel bound to reflect on what it was like, being a single working mother during the French Revolution. Olympe de Gouges, widowed at twenty, her son just one year old, brought him up by herself in Paris while pursuing her career as an actress, then a playwright, and later a political writer. She made sure to pay for him to have private tutors, and may have had help from her sister, also in Paris, to look after him. We know that he came with her to theatrical rehearsals, and eventually became an actor in her troup. By the time she died he was married with one child and another on the way. Under pressure (and perhaps torture) he signed a letter renouncing his mother. A few years later, he wrote and signed a document recusing himself, which he sent to the government, along with two volumes of his mothers' works. Pierre Aubry, Olympe's son, struggled to make a career for himself under Bonaparte, but eventually was sent by him to French Guiana, in South America, at the time slavery was being re-introduced there. Aubry died a few months after arriving, of malaria. His wife remarried, several of their children survived and some of their descendants still live in Australia and the United States. Mary Wollstonecraft found herself pregnant by her American lover during her stay in Paris, and moved alone to Le Havre when her baby girl, Fanny, was born. There she looked after her daughter while writing up her History of the French Revolution. By the time Mary and her daughter came back to England, the relationship with Fanny's father, Imlay, was over. In order to keep them out the way, he asked Mary to go and investigate the disappearance of a cargo of silver on the coast of Norway. Mary went with her daughter and a French maid, clearly not thinking of single motherhood as a reason not to travel. When they came back, Imlay made it clear that he had no intention of spending time or money on his daughter. Mary responded by attempting to commit suicide, leaving the following note for her daughter: I have long determined that the best thing I could do was to put an end to the existence of a being whose birth was unfortunate, and whose life has only been a series of pain to those persons who have hurt their health in endeavouring to promote her welfare. Perhaps to hear of my death will give you pain, but you will soon have the blessing of forgetting that such a creature ever existed. When Mary met her William Godwin, they agreed that he would act as her daughter's father. Unfortunately, she did not live long enough to find out whether that model of parenting would have been a success. Fanny Wollstonecraft did not live a happy or successful life. She lost her mother at the age of 3, and was left in the care of the father of her new sister, Mary. William Godwin remarried a few years later and Fanny and Mary were looked after by their step-mother who cared more for her own daughters than for them. Godwin, although he saw it as his duty to care for Mary's daughter, did not think much of her: My own daughter is considerably superior in capacity to the one her mother had before. Fanny, the eldest, is of a quiet, modest, unshowy disposition, somewhat given to indolence, which is her greatest fault, but sober, observing, peculiarly clear and distinct in the faculty of memory, and disposed to exercise her own thoughts and follow her own judgment. Mary, my daughter, is the reverse of her in many particulars. She is singularly bold, somewhat imperious, and active of mind. Her desire for knowledge is great, and her perseverance in everything she undertakes is almost invincible. My own daughter is, I believe, very pretty; Fanny is by no means handsome, but in general prepossessing. When the girls were teenagers, Percy Blithe Shelley came into their lives and seduced Mary by talking to him about her mothers' life and work. Two years after Mary ran away with the poet, Fanny, left alone with her unkind stepmother and a stepfather who did not care much about her, committed suicide. She was 22.

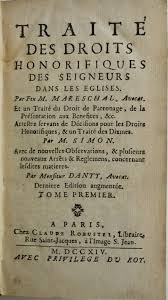

Sophie de Grouchy was widowed at 30, her only daughter still a toddler. Although she had a support system – her sister and an old nanny – to help her bring up young Eliza, she had to earn the money to feed and house her extended family, and she did that by painting portraits. Eliza Condorcet O'Connor is the one real success story of the three. This is perhaps due to the fact that her mother did not die when she was a toddler and was not tried and executed, thereby ruining her family's reputation and career prospects. By the time Eliza was old enough to marry, her mother had regained most of their family wealth and was able to purchase Mirabeau's old castle for her. Eliza seemed to have lived a long and happy life there, continuing the work her mother had started of editing her father's works. Her descendants still live at the castle On 6 August 1789, the Assemblee Constituante met to discuss the points that were made on the night of the 4thregarding the abolition of the privileges of the aristocrats and the clergy. One point of contention was the abolition of the 'droits honorifiques' i.e. rights and privileges that could be purchased by families or individuals within the church. These rights pertained to being seated in a particular place, burial privileges, having prayers and masses told, the use of incense and holy water, etc. Every aspect of church going could be moneyed.

These rights had to be abolished for the sake of equality – but at the same time, some families had invested in their church for several generations and there were contracts at stake that would have to be reneged on if these rights were abolished. The question of church privileges seems like a petty concern to us – not what the Revolution, in its early days ought to have been about. Yet the Assembly, fired up by the night of the 4thaugust, decided to spend an entire day discussing just that. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed