|

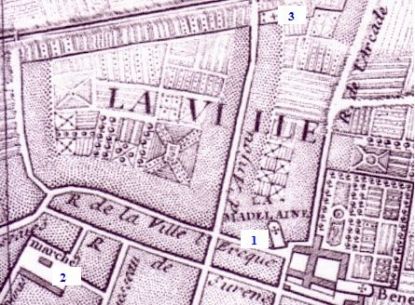

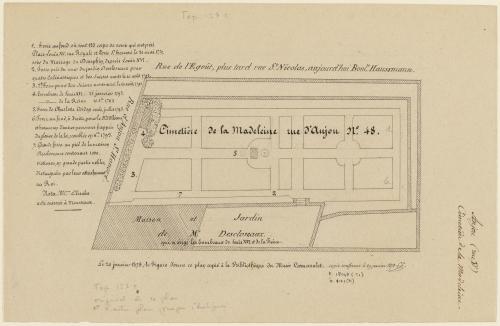

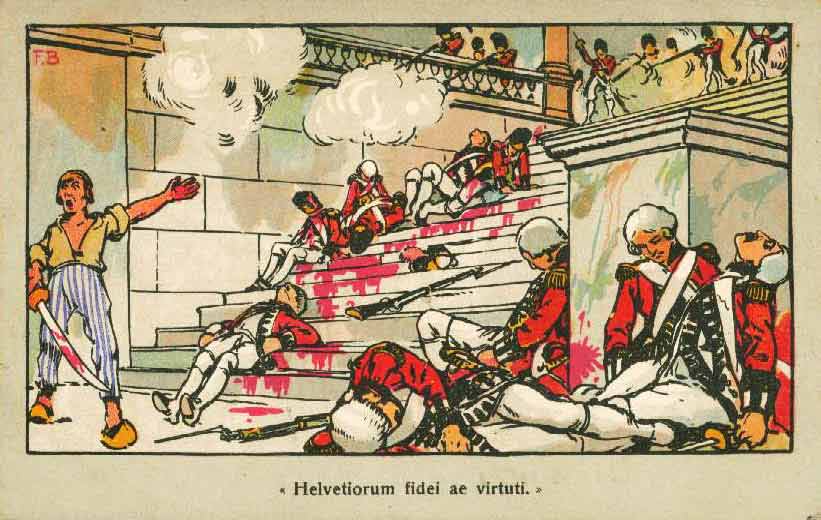

The revolutionary period, in particular the Terror, was hard on the Paris graveyards. Many people died in massacres and at the Guillotine who had to buried in the already full graveyards. When the body counts started to rise, the Parisians needed somewhere to pile up their dead. The site of the church of Sainte Madeleine, first opened in the 13thcentury was located roughly where 8 Boulevard Malherbes now stands. It had a very small cemetery and a slightly larger one was built in 1690, on land that was closer to the Faubourg Saint Honore, already a posh neighborhood. In 1720, the cure of la Madeleine sold a large tract of land to be convereted to a graveyard. The graveyard was built on a large rectangle of 45 by 19 meters surrounded by a wall. It filled up slowly at first, but in 1770 it received its first mass burial. On the occasion of the celebrations of the wedding of Louis the Dauphin and Marie-Antoinette, a show of fireworks was given to the people of Paris. This was a novelty, and more scary than exciting for many. There was a crush in the crowded streets and several hundred people died. These were buried in the Madeleine. The next large scale burial happened in August 1792, when the Paris revolutionaries, assisted by the Marseillais massacred the King’s Swiss Guards. Their mutilated bodies were thrown into the Fosse Commune at the Madeleine. By then it was summer, and the smell in the neighborhood became unbearable – someone reported it at the assembly, but it was decided that the risk of false rumours of a plague epidemic was too great if a fuss was made, and the subject was dropped. The rich inhabitants of the quartier would just have to put up with it. The location of the Madeleine was also very convenient for transporting bodies from the Place du Carousel and Place de la Revolution – the guillotine’s first two locations. Légende - Au recto, à gauche sur l'image, à l'encre, inscriptions correspondant à la numérotation de l'image : "1. Fosse au fond où sont 133 corps de ceux qui ont péri / Place Louis XV, rue Royale et Porte St. Honoré le 31 mai 1770, / soir du Mariage du Dauphin, depuis Louis XVI." ; "2. Fosse près du mur du jardin Descloseaux pour / quatre Ecclésisatiques et 500 Suisses morts le 10 août 1792." ; "3. 2e. Fosse pour 500 Suisses morts aussi le 10 août 1792" ; "4. Tombeau de Louis XVI. 21 janvier 1793. / -id- de la Reine 16 8bre 1793" ; "5. Fosse de Charlotte Corday seule, juillet 1793." ; "Fosse au fond, à droite, pour le Dc. d'Orléans / et beaucoup d'autres personnes frappées / du glaive de la loi ; comblée en Xbre. 1793." ; "7. Grande fosse au pied de la maison / Descloseaux contenant 1000. / victimes, en grande partie nobles, / distinguées par leur attachement / au Roi. / Nota. Mme. Elisabet / a été enterrée à Mousseaux.". Date et signature - Au recto, en bas à droite, à l'encre brune : "copie conforme le 29 janvier 1878 LL". - From the Musée Carnavalet. Eventually, in March 1794, the Madeleine was closed and the next victims of the Guillotine were buried elsewhere. But before then, more famous bodies were entered there, including the King and the Queen, many of their supporters and family members, Charlotte Corday – who benefitted from a single occupancy plot, the twenty-two Girondins (including Brissot) who died on 31 October 1793, and of course Manon Roland and Olympe de Gouges.

During the restoration, Louis XVIII built a chapel to the memory of his brother and sister in law. Small chapels were added later to commemorate the other victims of the Revolution.

0 Comments

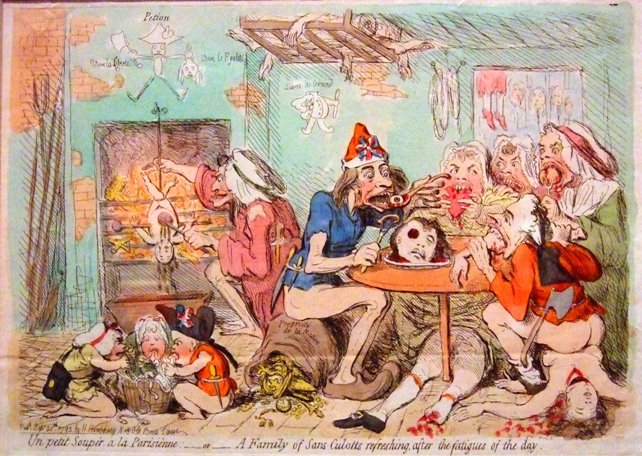

On the afternoon of 2 September 1792, the Tocsin was rung, and and canon was shot as an alarm. Word was out that France had lost Verdun, and the traitors to the republic were blamed - they must have spread intelligence. Who were the traitors? Mostly two kinds: the aristocrats, and the priests who had refused to pledge allegiance to the new civic religion, known as the refractory priests. But most of those were in prison. Manon reports the following anecdote: her husband was then minister of the interior, and one of his deputies came to alert the Paris Commune that some of the prisoners might be at risk. Danton replied testily: "I don't give a fuck for the prisoners or what happens to them!" (Portrait de Danton). There was indeed cause for worry: the last time the tocsin was rung and the canon shot was the 10 August, when the Parisians stormed the Tuileries, where the King and his family was held, and massacred the Swiss guards who were there for their protection. The King and Queen were now at the Temple prison, and quite safe for the time being. But the Swiss guards that survived, and some of the nobles of their entourage, such as the Princess of Lamballe, were in the Paris prisons. By the evening of 5 September, most of them were dead. The British Caricaturist James Gilray published the following picture of a sans-culotte (here depicted literally without trousers!) family eating the flesh of their victims after a day of murders. Unfortunately the caricature was not as far from the truth as it might have been, as Manon reports to a friend a few days later. "If you knew the horrible details of these expeditions! Women are brutally raped, before these tigers tear them apart, entrails are worn as ribbons, human flesh eaten, still bleeding! You know my enthusiasm for the Revolution, well, I am ashamed of it. It has been stained by scelerats, it has become ugly!|"| (letter to Bancal, 9 September 1792)." This episode marked a turn in the Revolution. Those who had been critical of the Commune, or Robespierre, Danton, and Marat - "My friend Danton leads all, Robespierre is his dummy, Marat holds his torch and his knife." - were now reluctant to have anything to do with them. By January, Roland had handed in his demission from the ministry, on 1 June, his wife was arrested, and on 2 June a decree for the arrest of the Girondins was issued. By November, all were dead. "The whole of Paris let it happen... the whole of Paris is damned in my eyes, and I no longer hope that liberty may take root amongst such cowards, insensible to the worst outrages inflicted on nature and humanity, cold spectators of attacks that could easily have been prevented by fifty armed men." (Memoires) |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed