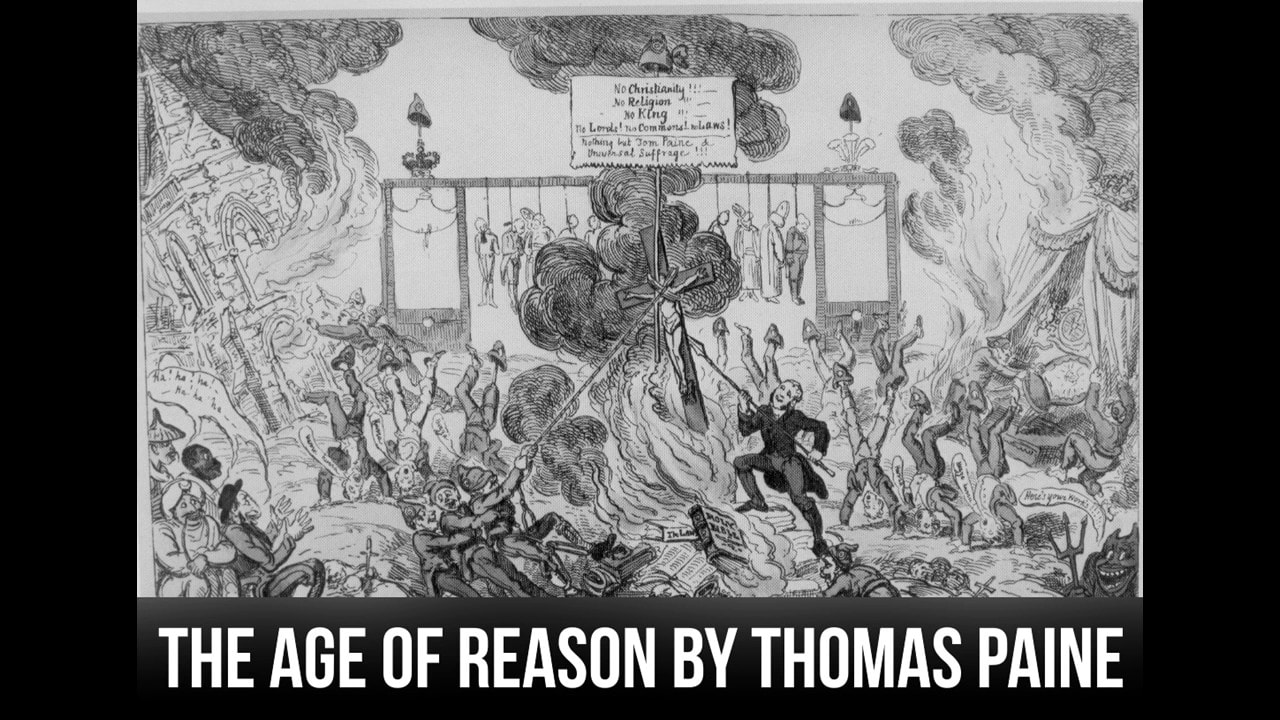

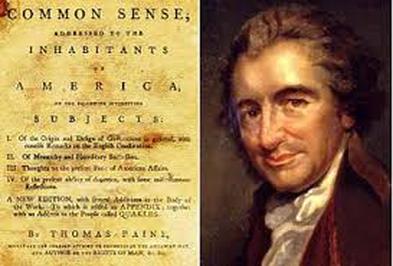

I am not become an Atheist, I assure you, by residing in Paris Mary Wollstonecraft wrote these words in a letter to Joseph Johnson, her publisher, on 15 February 1793, after she had resided in Paris for two months. She had travelled to Paris with a commission to write a series of letters on the French Revolution. Wollstonecraft had come to Paris at the beginning to the reign of Terror. A few months before her arrival, mobs had butchered aristocrats in their prisons, priests and nuns in convents and monasteries, supposedly on the order of Danton. The first few weeks of her stay had themselves been momentous: the King of France had been tried by the people, condemned to death and executed. She had the seen the king drive past her window on his way to his trial, just a couple of weeks after she had settled in Paris. But even without the growing atmosphere of terror Wollstonecraft would have found it hard to settle in Paris: her French, while good enough for reviewing and translation purposes, was not really up to making conversation, and she was here alone despite having originally planned to travel with friends. Perhaps it is not surprising that her first impressions should be negative, bordering on the depressive. It would not have been surprising either if she had begun to lose her faith. Another factor in a possible - but not actual - loss of faith, was that her friends, the Girondins, were almost unanymously atheists. Condorcet and Grouchy were, as was Brissot, as were the Rolands. Perhaps this was a Parisian thing, then, as Wollstonecraft's other republican foreign friend, Thomas Paine, was certainly not an atheist. In his Age of Reason, written during his incarceration at the Palais du Luxembourg, he not only deplores his friend's atheism, but attempts to convince them, through argument, that it is perfectly possible to follow the dictates of reason and the Enlightenment without falling to the extremes of atheism.

0 Comments

« I am not become an Atheist, I assure you, by residing in Paris ».  The atheis Cult of Reason, which preceded the theist Cult of the Supreme Being, imposed by Robespierre. The atheis Cult of Reason, which preceded the theist Cult of the Supreme Being, imposed by Robespierre. Mary Wollstonecraft wrote these words in a letter to Joseph Johnson, her publisher, on 15 February 1793, after she had resided in Paris for two months. She had travelled to Paris with a commission to write a series of letters on the French Revolution. Wollstonecraft had come to Paris at the beginning to the reign of Terror. A few months before her arrival, mobs had butchered aristocrats in their prisons, priests and nuns in convents and monasteries, supposedly on the order of Danton. The first few weeks of her stay had themselves been momentous: the King of France had been tried by the people, condemned to death and executed. She had the seen Louis drive past her window on the way to his trial, just a couple of weeks after she had settled in Paris. But even without the growing atmosphere of terror Wollstonecraft would have found it hard to settle in Paris: her French, while good enough for reviewing and translation purposes, was not really up to making conversation, and she was here alone despite having originally planned to travel with friends. Perhaps it is not surprising that her first impressions should be negative, bordering on the depressive. It would not have been surprising either if she had begun to lose her faith. Wollstonecraft's republican friends, the Girondins, were mostly atheists, Grouchy and Condorcet were, the Rolands were, as was Brissot. It seemed that for many French republicans of that time, the rule of reason precluded the belief in God. This may well indeed have been a Parisian thing. Thomas Paine, also ally to the Girondins, was not an atheist either. But he described the French of that time as ‘running headlong into atheism’, and saw his role as their friend to persuade them to give up such silliness. In the Age of Reason, which he wrote while incarcerated in the Palais du Luxembourg, he attempts to divert the French from the path of Atheism, showing them that one could be reasonable, defend the values of the Enlightenment and of the revolution, while still believing in God.

According to Brissot, both the English revolution and Macaulay’s History were a significant influence on the American Revolution: The Americans lit their reason with the torch of those men, who were enlightened in a century when nobody was. It is enough to be convinced of it to read the excellent history of Miss Macaulay, and to compare what this excellent woman says about the sevellers(sic) whose principles she set out so well, to all the public writings of Americans during the troubles. Macaulay, encouraged by the warm friendship of her correpondents, and the success of her history in America decided to travel to that country, for the purpose of writing about the American Revolution. During that time she was hoping to gather material for her book, but also to find support for the publishing of it. In that, Brissot tells us, she was disappointed: She was admired everywhere she went, but no one paid a subscription for her History. Deceived in her speculation, and in the support she had excepted, she came back discgusted by the Americans. Her anger was unfounded. At peace, empoverished Americans only thought of rebuilding their farms and cultivating their lands. They only read newspaper, which, despite their cheapness, they could ill afford. Few books, aside from the Bible, were being sold in America, and if you look at the list of subcribers for Gordon’s History of America, you will be surprised to find that three quarters were English. Macaulay died shortly after her trip. One might be tempted that she would have received more support had she been a man – she could, like Paine, have become the cossetted darling of the Americans. However, Paine went to America before the war, before the Americans became strapped for cash. Brissot experienced something similar to Macaulay – when he travelled to America to find a place to settle with his family, he tried to enlish patrons, people who would help him establish himself there as a writer. He too came back disappointed.

Jacques-Pierre Brissot, Manon Roland’s close friend and republican ally, also visited England. Brissot was a lower-middle class provincial who trained as a lawyer, but came to Paris and decided to become instead a writer and journalist. One of his first jobs was for the Scotsman Samuel Swinton, the editor of the Courier de l’Europe which reported on English politics in several languages. Brissot was his French editor. It is in that capacity that he first travelled to England in 1779 at the age of 25. This first journey was short – two weeks – but it gave him a taste for England. This taste became more pronounced as the young writer came up against the stringent French censorship laws, and again when in 1782, he married Felicite Dupont, who translated English writers Goldsmith and Dodsley, and who had spent some of her childhood in London. The couple moved to London shortly after they married. Brissot, who was hoping to establish himself as a writer there was disappointed. As a foreigner, I was snubbed, he says, except by a few individuals, the principal one being Catharine Macaulay. Catharine Macaulay (1731-1791) was only fifty-one when Brissot met her. Yet, he describes her as a very old woman: Imagine a woman with lead on her face, missing teeth, wrinkles badly hidden with rouge, and whose decrepitude showed beneath her always fashionable and elegant get up. Next to her the brilliant figure and freshness and health of her husband, still an adolescent! It looked as if a child was hugging a corpse. Macaulay’s marriage to a twenty-five year old (hardly a teenager!) and good looking man had of course been badly received, and even Brissot, who admired her greatly and defends her against other accusations (such as that she was not the author of her own works) finds this difficult. But even then Brissot tries to dispel the calumnities by arguing that it was the family of her husband (his brother was some sort of medical innovator or quack) that was really objectionable. Macaulay’s most famous work was her History of England in eight volumes. Brissot thought that work remarkable, and beleived that she deserved the laurels she had taken from David Hume. To objections that she could not, as a woman, really be the author of that work, Brissot replied that the evidence that she was laid in her conversation: ‘It has all the characteristcs, he said, of the dignity, the republican energy breathed by her History.’ In 1784, Manon travelled to England with her husband who was to meet professional contacts there. They came by water, first taking a river boat from Amiens to Boulogne, and then a ship with ‘two rooms and six beds’ for a ten hours crossing to Dover. From there they made their way to London, stopping on the way as tourists would. Dover, by Thomas Girtin (1775-1802) Manon is very enthusiastic about what she sees. The English countryside is pretty! It’s clean! And it is welcoming to travellers, with walking paths readied and lands separated with 3-foot hedges rather then 12-foot walls as they are in France. In London she finds the Strand, with Somerset House nearly finished, to be a most beautiful avenue, and again, clean – even the market displays of fish and meat are tidy and appealing. St Paul’s cathedral is like nothing she has ever seen, and she loves Westminster, the Abbey and the Palace. The British Museum with its displays of insects, organized along the Linnaean classifications, and its display of Egyptians mummies is fascinating. The Rolands seat in during parliament, and hear Pitt the young and Fox arguing. They travel to Kew and see the gardens there – what a poor job they did of copying them at Ermenonville, where Rousseau is buried, she thinks. She is taken by how the women live. They are separate from the men – their domain is the home and they accept that their job is keep the house in order and the children clean. They do not gamble. They are also more modest – and cleaner! – than their French counterparts. They wear a scarf over their décolleté, and a bonnet or kerchief at all times. Young women are not shown in society till quite late, and they do not powder their till they are between 15 and 18. Unlike their brothers, they are not sent to schools – except for a few, but these are respectable schools – but their mothers teach them all they need to know. But mostly she is impressed by the air of liberty (and again cleanliness!) that she sees about her, whether in the landscape or the education of the young: Liberty and cleanliness: here are the two laws of early childhood. Children are washed, every day, from head to toe; they do as they wish, as long as they cause no harm. We would be surprised to see at the table of a Duke his children, aged 8 or 10, pushing their plates in front of them, putting their elbows on the table and resting their on their hand, or other such things. They do not pay attention to such trifles as they know that later, the child will notice that these things are not done, and will correct herself for the sake of their own well-being. From this method in general it follows that children are themselves in front of their parents, they do not feel embarassed by their presence, and their parents know them better. It also follows that children are more natural, free, and confident in their movement, their demeanor, which becomes permanently imprinted and suits well the pride of a republican and the independence of a man. Thomas Paine first arrived in France in 1787, and he moved between there and England until his arrest in December 1793 and release from prison some months later, upon which he moved back to America. In August 1792, Paine was granted honorary French citizenship, alongside a few foreign supporters of the revoluton. Paine already had two citizenship: English, from birth, and American, also honorary. Paine was connected to the Girondins, and during Roland’s ministry, he visited Jean-Marie and Manon at their Paris home. Manon reports on his character in her usual style: I have already named the most notable of the people I entertained, but I must also mention Paine. He had been given French citizenship as one of the celebrated foreigners whom the nation felt proud to adopt, being noted for his writings which had played a large part in the American Revolution and might have helped to bring about a similar revolution in England. I cannot form an absolute judgement of him because he could speak no French though understood it and I was such in much the same position with English; so that although I could follow his conversation with others I could hardly engage him in one myself. But I did form the impression that, like so many authors, he was not worth so much as his writings. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed