|

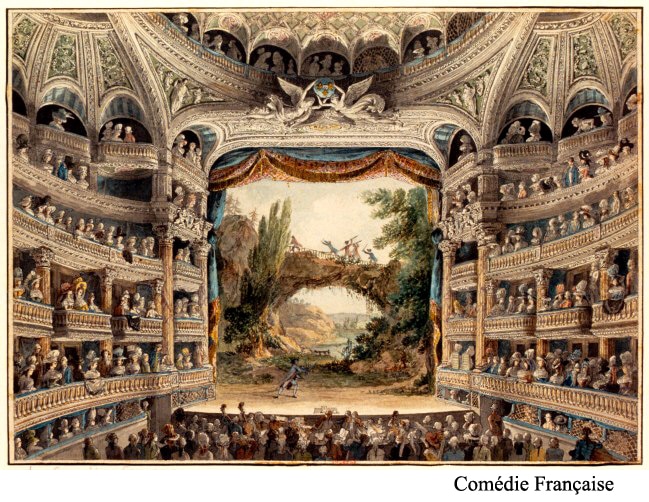

Olympe de Gouges, when writing her play about slavery, Zamore and Mirza, or the Fortunate Shipwreck, displayed a certain amount of confusion about the geographical setting and the people she depicted. The play is described as an Indian drama. The Action is said to take in the East Indies. The main characters, Zamore and Mirza are described as Indians and another as governor of a Town and a French Colony in India. There are also 'several local indians'. Gouges describes a ballet that is take place at the end of the performance where Indians and soldiers mix, and which is to represent the discovery of America. In a postcript she added to the play, she recommended that the theatrical company 'adopt both the colour and the dress of the Negro.' thereby contradicting apparent claims that her protagonists are either Asian or native Americans. Although the French did colonize India, it is not clear that this is supposed to be the setting of the play. Rather, the West Indies is where the French had slaves. What about East Indies? The French did again colonise Vietnam, then Indochina, but this was not where the slave trade was conducted. On the other hand, the French East India Company had interest in Mauritius and Reunion (Ile de France and Ile de Bourbon), both, in the West Indies. The proximity of the West Indies to America may have led to the idea of a ballet re-enacting the discovery of America. What can we make of such racial ignorance and inept geography? Of course Olympe was largely uneducated. And the anti-slavery movement in France was yet to grow strong enough that many people were aware of the specifics of the slave trade and of the conditions of living in the West Indies. In fact, Gouges was one of those who helped bring the evil of slavery to the attention of the French public, and Brissot, one of the founders of the Club des Amis des Noirs, claimed to be influenced by her play, and offered her a membership to the abolitionist club as soon as it was founded. Olympe was ignorant, but she did not, as an 18th century woman, have much of an opportunity to educate herself by travelling. She was confused, but had good intentions: she felt that by portraying courageous, intelligent and compassionate runaway slaves, she would spread the word about the abuse that was perpetrated and interest the public in helping stop that abuse. Poor education, lack of opportunity, good intentions all sound like the sort of excuses given for every day racism and cultural appropriation. Does it make sense to see in Zamore and Mirza the beginnings of these phenomena? Ballet - at the end of the last act.

0 Comments

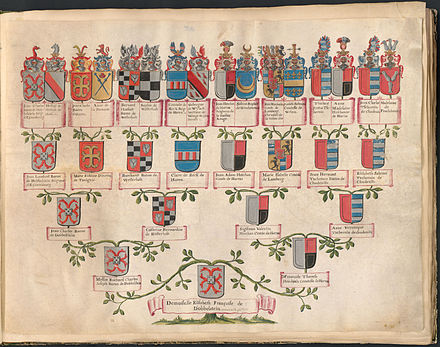

When Sophie de Grouchy was young, no tutor was assigned to her. But she benefitted from her mother's instruction, a woman known for her intellect, culture and generosity. And she was allowed to participate in her younger brothers' lessons. She did so well at this that when their tutor was sick, she took over their Greek and Latin instruction. At the age of 18, she was sent to a finishing school in Normandy, at Neuville-les-Dames, near Macon, a secular convent for ladies. She received the title of Chanoinesse, and was addressed as Madame. In order to gain admission, one had to pay a substantial fee and maintenance amounting to 9000 pounds per year, but also provide proof of lineage: 9 generations on the father's side and 3 on the mother's. The convent was not ostentatiously religious. Pupils studied Latin and modern languages, and worked on their accomplishments. They hosted parties, the purpose of which was to find husbands of the right sort. In an environment that was religious and socially privileged, she became an atheist and socially aware. She discovered Voltaire and Rousseau, she read and translated Tasso's Jerusalem, and an unnamed work by Young (probably his Tour of Ireland). Her aunt, visiting her, worried about her health - her eyes were puffy every night and ached so that she feared it might be a form of gout. And yet Sophie kept on with her work.

The building Sophie lived in is long gone. But Neuville now has an Allee Sophie de Grouchy, on which stands an elementary school, l'école Condorcet. There are many schools named after Condorcet in France, but if this one is named after the Marquise, not the Marquis, then it is, as far as I know, unique. As most Parisian children of the times were, Manon was sent to spend her first two years in the home of a wet-nurse, in the country side. Perhaps Paris was not a great place to bring up a baby, and Marie-Jeanne’s parents had already lost several children, so they were bound to be more careful. Fresh air, a nurse who has nothing to do but fuss over her, this would keep her alive, make her healthy and strong. And whether or not from the effect of her residence in those first two years, Manon, as her mother called her, was healthy and strong, and would no doubt have lived well beyond the age of 38, had she not been guillotined. When she came back it was not to the Ile de la Cite, but on the other side of the Pont Neuf, Quai de l’Horloge. Young Manon had the run of her father’s library – not a large one – and on certain days, she has the run of the town. She has tutors – no expense was to be spared in the clever child’s education. She knew her catechism by heart but was not convinced by what she learned. On Sundays, she hid a favourite book in the cover of her bible: Plutarch’s parallel lives, translated into elegant French by Anne Dacier. She embraced republicanism, admiring the values and virtues of the Roman leaders she read about. She began to wish she had been born Roman, or above all a man, so she could act on her convictions. But soon even Plutarch was no longer enough. She wanted to learn more and her tutors – music, languages – could not teach her enough.

When Manon 11 an apprentice of her father assaulted. The experience shocked her deeply and she sought refuge in religion. Manon begged her parents to be allowed to continue her studies at a convent school on the Ile de la Cite. But at the Convent of the Augustines, Manon, a precocious child, turned out to be difficult to teach, as she knew more already than the kindly nuns who’d agreed to take her on. She stayed a year, and made lifelong friends there, two of whom, the Cannet sisters, became her correspondents and later introduced her to her husband to be. In the 1750s, when Marie Gouze, as she was then called, was of the age to learn how to read, the education of French children was under the control of the catholic church. There were few options: you could be educated at home, privately, by a parent or a tutor, or you could be sent to school. Boys who were not particularly rich, might do better at school than at home. Maximilien Robespierre, for instance, won a scholarship to leave his native Arras and study at the Lycee Louis le Grand, in Paris. But there were no equivalent schools for girls, so unless they could be educated at home, working perhaps with their father, as Anne Dacier had done, or with their brothers' tutors, as Sophie de Grouchy did, girls were sent to convents, or to the Ursulines' day Schools.

The Ursulines school at Montauban had been started in 1682, by six Ursuline sisters from Toulouse. Their school still stands - it has been expanded, and they now have a very modern looking building. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed