|

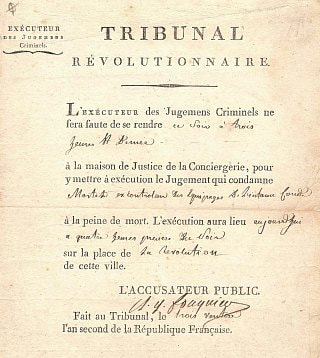

Olympe was tried at the Conciergerie on 2 November 1793. After she was arrested on 20 July she had been held first, at the Prison de l'Abbaye, transfered to the hospital prison of La Petite Force - she was suffering from an infected cut on her leg - and finally she paid to be incarcerated at a private pension on Chemin Vert. The public prosecutor of the Revolutionary Tribunal was Antoine-Quentin Fouquier-Tinvinlle, a zealous and ruthless officer of the Terror, who took his turn at the Guillotine in 1795. Olympe was introduced as 'Marie Olympe de Gouges, veuve Aubry. born in Montauban, aged 38 (she was in fact close to 45), residence: rue du Harlay section du Pont Neuf'. She was charged with' having composed a work contrary to the expressed desire of the entire nation', and according to Article 1 of law of 29 march 1793: Whoever is convicted of producing writings advocation for the dissolution of national representation [...] will be sentenced to death." she was sentenced to death by the guillotine. She would have been excecuted on that same day, but, after the order was read, she announced that she was pregnant. 'My enemies will not have the glory of seeing my blood flow. I am pregnant and will bear a citoyen or citoyenne for the Republic' According to the law, she was to be examined by health officers who had been named by Robespierre 8 months previoulsy, after the Revolutionary Tribunal was founded, and by a Midwife, Veuve Prioux. Her cell at the Conciergerie was the same one Marie-Antoinette had been held in after her attempted escape. It was isolated, for the purpose of keeping prisoners 'au secret'. The infirmary was just outside that cell, a dire place, if we are to believe the description of a surviving prisoner, Beugnot: Seven by thirty metres, closed on both sides by iron fences, two narrow windows, vaulted roof, like some sort of gothic hell. 40 or 50 dirty straw beds on either side, with two or three patients each, sharing unwashed blankets. The privies were in the middle of the infirmaries, and there sick patients who had collapsed on the way lay in their own waste. The corpses, three or four each day, were removed at a specific hour of day, and until that time, the dead remained in bed with the sick. All that is now left of this room is one of its narrow windows, which is visible from the women's courtyard. The medical team concluded that if Olympe was pregnant, it was too early to tell. Fouquier-Tinville chose to ignore their doubt, and declared that her claim had been found to be false: The Public Prosecutor notes that the accused was incarcerated for the past five months and that according to regulations no contact was allowed between men and women in prisons. Therefore she made it up in order to avoid the death penalty. There was in fact much romantic commerce between prisoners, as they were kept in adjoining wards, and often not very efficiently. In any case, Olympe had been staying in a private pension for mixed prisoners, a fact that Fouquier Tinville chose to ignore.

2 Comments

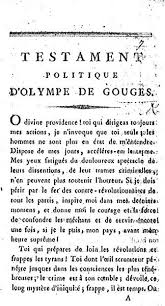

Olympe was arrested on 20 July 1793. Three weeks before that, she was moving her furniture from Paris to a small house she had bought in the countryside near Tours, and where she was about to retire. She had been away visiting properties and spending time with her son, but had come back to Paris to see to the removal of her things. Olympe knew that by being in Paris, and publishing more political tracts, she was putting herself at risk. But the decree against the Gironde had just been issued and she felt she had to do something. Her Political Testament, written at time, reflects her anger and uneasiness: If, in a final effort, I can still save the republic, (chose publique), I desire that even while they immolate me to their fury, my sacrificers still envy my fate. And if one day, posterity notices women, perhaps the memory of my name will be of value. I have planned everything. I know that my death is unavoidable, but how beautiful and glorious it is, for a well-born soul, when ignominious death threatens all good citizens, still to give one's life for our dying country! Her next tract, The Three Urns, is an attack on the Paris Commune. It is printed by her imprimeur, Longuet, on 15 July. He draws 1000 copies. She sends a copy to the committee of public safety, and one to Herault de Seychelle, then she waits a few days - no reply, which she takes to mean that she can go ahead. Her distributer, or afficheur, is a Citizen Meunier who lives in the Rue de la Huchette. On 20 July, Olympe leaves her apartment on the Ile de la Cite, crosses the bridge St Michel, and turns left into the Rue de la Huchette. The Pont St Michel and the Rue de la Huchette are still there. The actual Pont St Michel dates from the mid-nineteenth century. Earlier photographs show a similar looking bridge, with four arches, rather than two, and less flat. And back in the eighteenth century, it would still have had the more traditional aspect of the Medieval bridge, it would have been covered in wooden shops and houses. The members of the Commune are reputed to have met in a tavern on the Rue de la Huchette. If true, this may well have influenced Meunier's decision not to post Olympe's Three Urns. What he actually told her, on the morning of her arrest, is that he was worried that it would rain. One imagines Olympe looking up at the clear sky, puzzled, before she set out to find another distributor on the Pont St Michel. But when she got there, Meunier's daugher, who had followed her pointed her out to three policemen and members of the national guard, She was arrested her and taken to the Depot prison of the Mairie.

Olympe de Gouges was brought in to the Prison de l'Abbaye three weeks after Manon. The two must have overlapped, for a few days and maybe they talked, exchanged a few pleasantries. But Olympe was not the kind of woman Manon liked to talk to, not respectable enough, not mindful of her virtue or reputation. In any case, it’s unlikely that Olympe was in a talkative mood. A week earlier, she had cut her leg, falling off a car, and the wound was infected. The guardians at l’Abbaye decided they could keep her – it would not do for a prisoner of as high a profile as Madame de Gouges to die before she was tried. So she was transferred to another prison, the Petite Force, previously a prison for prostitutes, and the scene of the Princesse de Lamballe’s massacre the previous year, but now converted to an infirmary for prisonners. No doubt the conversion didn’t amount to much and Olympe did not want to stay there. She sold her jewels and paid to be transferred to a private pension for sick prisoners on the Chemin Vert. Unlike the Abbaye or the Force, this is a prison for both men and women, and soon, Olympe finds herself pregnant at the age of nearly forty-five. Only three weeks afterwards, on 28 October Olympe was taken to the Conciergerie and put there in isolation for four nights in the same cell where Marie Antoinette had spent her last days, just two weeks previously. Then on 2 November, she is tried. As she is accused of having printed a pamphlet against Robespierre, raising the possibility of a constitutional monarchy, she cannot plead innocent. Not only had she written the pamphlet in question, the Three Urnes, but she had herself posted it on the walls of Paris, after her distributor deserted her. So instead of pleading innocence she pleaded pregnancy. She was examined and the doctors confirmed that there was a good chance she might be pregnant - but it was too early to tell. She herself testified that she recognised the signs, that had felt the same way on the two occasions she'd been pregnant before. (This is, incidentally, the only mention of a second child, who must sadly have died). Her prosecutor, the infamous Fouquier-Tinville, however, refused to consider the evidence on the grounds that she had been in a female only environment (conveniently forgetting her stay at the Chemin Vert pension). The next day, Olympe climbed the stairs up to the Rue de Mai, stepped into the charette, and was driven to her execution. Her last words: “Children of France, you will avenge my death!”

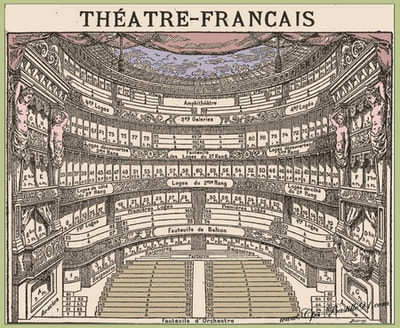

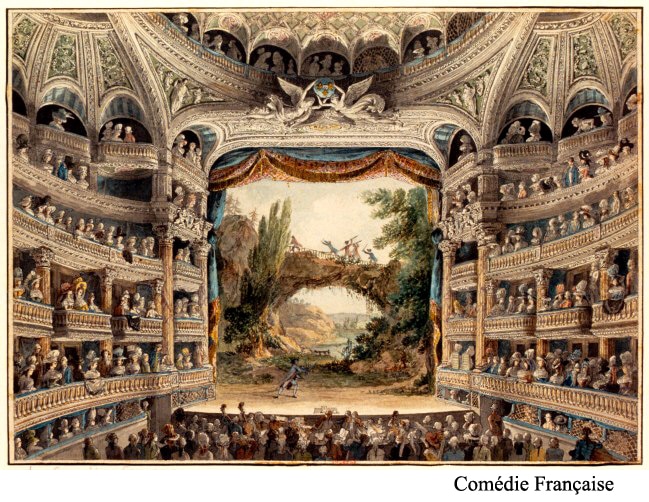

Some male French historians, it seems, still are not very comfortable with the idea that a number of women played a significant role in history. Olivier Blanc, who wrote an excellent biography of Olympe de Gouges is not one of them. And perhaps it is that my sample is small, and it is definitely old. For the bicentenary of the 14th July, Pleiade came up with a small illustrated volume about the writers of the Revolution. The editor of the volume, the essayist Pierre Gascar (1916-1997), managed a very respectable selection of male writers, and wrote about the with the reverence they deserved. One gets the feeling that even the most psychopathic amongst them have to be treated fairly - after all, they played a role in the revolution that shaped the French nation we know and love. What he did not do, however, was waste much time on the women writers of the period. Except for one, who is mentioned on nine (four of which are pictures) occasions, with one fairly long section in which her name recurs, and the others passing comments. That was Olympe de Gouges. In two of the passing comments, Gascar uses the adjective 'ardante' to describe her. That is, Olympe de Gouges, was 'fervent' or 'passionate'. She was also, driven to a near 'delirium' by her attempt to assert herself in the political scene. She was, Gascar tells us, led in all things by the desire to succeed, and the need for glory. But because she was a woman, he concludes, she presented a 'disarming' picture of the thirst for fame. Her writings did not reflect her judgments, but rather her sentiments. Her objection to putting the king to death was not based on any belief that this could harm the revolution, or that it would be morally wrong, but on disgust. Lucky for her, she is not the only woman philosopher of the revolution to have been portrayed as a passionate figure driven by ambition but incapable of judgment. In 1927, Jean Martin, writing about this all but forgotten (because largely insignificant) member of the Girondins, Achille Duchatellet, describes Sophie de Grouchy as a 'fiery head'. He derives this description from one by her friend Dumont, who wrote about Sophie that she had : A serious character, a mind that flourished on philosophical meditations, republican readings, and a passion for Rousseau's works had inflamed her head. Describing a letter Sophie wrote to Dumont about the state of French politics after the massacre of the Champs de Mars, Martin alerts to the overflowing feminity of the letter, and the instances of 'coquetry' that fill in the spaces between the writers' attempt to engage with the political thought of her time. But, Martin notes generously, she does make a sensible point in passing, about governments in general presenting an obstacle to enlightenment. The rest of her descriptions, however, only serve to 'stir her nerves' because she dreams of a moving persecution of which she would be the heroine. Her thoughts on the subject of how to educate a reasonable woman are the occasion for Martin to show us that Sophie is vain - she must be the reasonable woman in question. She is also, he notes, being ridiculously unfair to Dumont, when she notes that it will be a while before men treat women as reasonable being ('Not all men!). This, is the sort of drivel that we have to wade through in order to study the history of women philosophers. It is a research project all by itself, and I suppose as such interesting. But it leaves a very unpleasant taste. At the end of a treatise in which she takes on Rousseau's analysis of human progress, Olympe de Gouges makes the following proposal: a second French theatre, or The National Theatre. A great number of well-born women are ruined because men, who have seized everything for themselves have prevented women to elevate themselves, and to obtain for themselves useful and lasting resources. Why should my sex not one day be rescued from this thoughtlessness to which their lack of emulation exposes them? Women have always written. They have been allowed to contend with men in the theatrical profession. But they would need proof of greater encouragement. Such is my plan: She goes on to describe an institution that would take in children from respectable but poor families, educate them in the arts and train them as actors, but always with a view to their respectability. After a few years, these children would constitute a troop of actors and would be offered the opportunity to produce plays. Those that chose not to, could pursue any other career in the arts. But as many of the fashionable plays of the times were not, to Olympe's mind, respectable, she would enlist the help of writers who are not given to scurrulous plots, and whose works are not usually performed, i.e. women. She says she herself has 32 plays ready to go, and that many other women have penned good plays.

Thus Olympe aims to kill two birds with one stone: Give women playwrights the chance to work, and reform the arts by providing a national artistic education so that would be artists do not resort to demeaning themselves in order to pursue their arts. Olympe de Gouges, when writing her play about slavery, Zamore and Mirza, or the Fortunate Shipwreck, displayed a certain amount of confusion about the geographical setting and the people she depicted. The play is described as an Indian drama. The Action is said to take in the East Indies. The main characters, Zamore and Mirza are described as Indians and another as governor of a Town and a French Colony in India. There are also 'several local indians'. Gouges describes a ballet that is take place at the end of the performance where Indians and soldiers mix, and which is to represent the discovery of America. In a postcript she added to the play, she recommended that the theatrical company 'adopt both the colour and the dress of the Negro.' thereby contradicting apparent claims that her protagonists are either Asian or native Americans. Although the French did colonize India, it is not clear that this is supposed to be the setting of the play. Rather, the West Indies is where the French had slaves. What about East Indies? The French did again colonise Vietnam, then Indochina, but this was not where the slave trade was conducted. On the other hand, the French East India Company had interest in Mauritius and Reunion (Ile de France and Ile de Bourbon), both, in the West Indies. The proximity of the West Indies to America may have led to the idea of a ballet re-enacting the discovery of America. What can we make of such racial ignorance and inept geography? Of course Olympe was largely uneducated. And the anti-slavery movement in France was yet to grow strong enough that many people were aware of the specifics of the slave trade and of the conditions of living in the West Indies. In fact, Gouges was one of those who helped bring the evil of slavery to the attention of the French public, and Brissot, one of the founders of the Club des Amis des Noirs, claimed to be influenced by her play, and offered her a membership to the abolitionist club as soon as it was founded. Olympe was ignorant, but she did not, as an 18th century woman, have much of an opportunity to educate herself by travelling. She was confused, but had good intentions: she felt that by portraying courageous, intelligent and compassionate runaway slaves, she would spread the word about the abuse that was perpetrated and interest the public in helping stop that abuse. Poor education, lack of opportunity, good intentions all sound like the sort of excuses given for every day racism and cultural appropriation. Does it make sense to see in Zamore and Mirza the beginnings of these phenomena? Ballet - at the end of the last act. In the 1750s, when Marie Gouze, as she was then called, was of the age to learn how to read, the education of French children was under the control of the catholic church. There were few options: you could be educated at home, privately, by a parent or a tutor, or you could be sent to school. Boys who were not particularly rich, might do better at school than at home. Maximilien Robespierre, for instance, won a scholarship to leave his native Arras and study at the Lycee Louis le Grand, in Paris. But there were no equivalent schools for girls, so unless they could be educated at home, working perhaps with their father, as Anne Dacier had done, or with their brothers' tutors, as Sophie de Grouchy did, girls were sent to convents, or to the Ursulines' day Schools.

The Ursulines school at Montauban had been started in 1682, by six Ursuline sisters from Toulouse. Their school still stands - it has been expanded, and they now have a very modern looking building.  A most fashionable way of thinking about politics in the 18th century, was to hypothesize what life would be like without any form of political government, and argue that it would intolerable, so that no matter how badly off we might be in this world, in a world without government, we would be worse off. This relied on the assumption that in the state of nature, we would be unhappy. As Hobbes famously put it, life in the state of nature would be 'nasty, brutish and short'. Rousseau is often portrayed as disagreeing with Hobbes on this. After all, the savage human being for him is carefree and happy, living in a land of plenty, and has no need for war or strife. But even Rousseau believed that as soon as one human being meets another, they become enemies, compete and war against each other. The only way out is civilization and government. One writer stands out in disagreement with this pessimistic view of humanity in its 'natural' state - or rather she would stand out if she were still read. Olympe de Gouges wrote a short philosophical treatise in 1788, in which she argued, against Rousseau, that human beings in the state of nature would have been, not only happy, but quite capable of living with each other, collaborating on projects and forming lasting loving relationships.

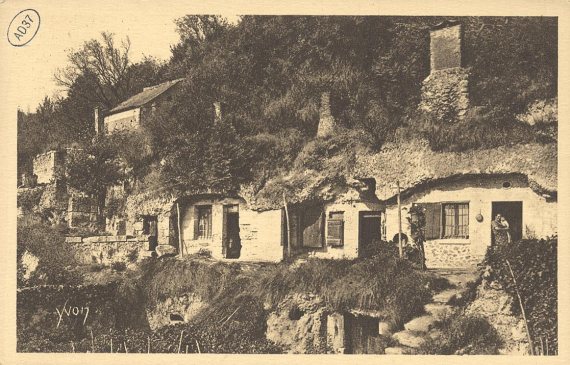

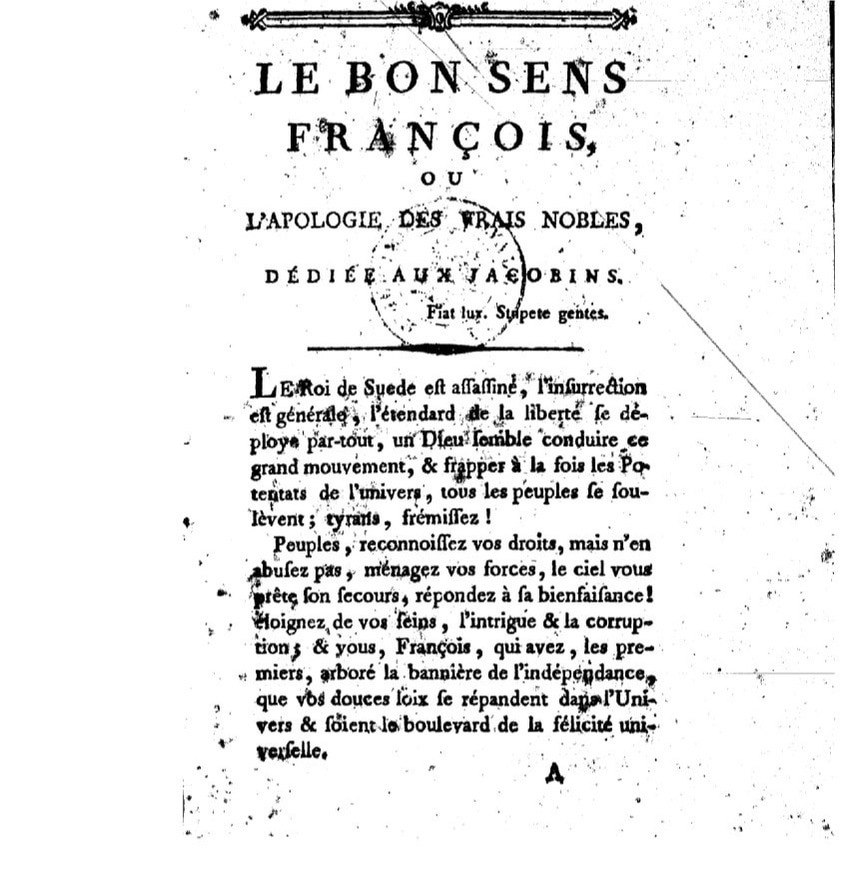

What does she base her belief on? Her own childhood experience of a simple, free and outdoors upbringing. In Le Bonheur Primitif, she speculates on the daily lives of the people Rousseau calls 'savages'. She surmises, for example, that the way in which the first breads were made may have been similar to how she was making bread as a child, laying the dough on hot ashes, and remembers how pleasant that experience was. This, she claims, gives her an insight into the lived experience of primitive people. Olympe de Gouges was in the habit of relating personal anecdotes at then end of her published texts. So for instance, the story of how she travelled from Auteuil to Paris, and the evidence that she corrected her own proofs is printed at the end of the Declaration des Droits de la Femme. In a 1791 text entitled "Le Bon Sens François" she tells an amusing story about what happened when she overheard two men in a coach talking about the famous author Olympe de Gouges. She interrupted the conversation: -"So you know her quite well?" - "Certainly. Her husband was a cook: she refuses to bear his name! No one knows who her father is. As to her works, not one word comes from her. She cannot read, they were written for her, affecting carelessness and ignorance in the style to make it seem that they are hers." - "But I have seen her draft a piece in front of several witnesses, and she even won a bet by doing so." Replied Olympe. - "Ah! Madam! The play was written for her in advance and she was made to learn by heart." - "Are you quite sure?" - "So sure that I am prepared to bet she could not do the same again in front of me. Besides I know what I am talking about - I am one of her fortunate admirers." Olympe gave her final reply as she was leaving the car: - "Sir, I have listened to your idiotic claims with the calm of a philosopher, the courage of a man and the eye of an observer. I am this same Olympe de Gouges that you never did know and never could. Take advantage of the lesson I am giving you: men like you are common enough, but women like me are the work of several centuries." [Dialogue adapted and translated from Olivier Blanc, Olympe de Gouges, p. 76.] In 1788, when Olympe de Gouges printed the first volume of her Works, she included a play titled Le Mariage Inattendu de Cherubin. This play had been written in homage to Beaumarchais's Marriage of Figaro, and Olympe was hoping to attract the great author's interest or patronage. Unfortunately all she attracted was his ire. Beaumarchais decided, without having read it, that her play plagiarized his and he instructed the actors of the French theatre, with whom he has a great influence, not to take it. Undeterred, Olympe decided that she would make the best of things and seek actual feedback from Beaumarchais on her work. She wrote him a note, and like Manon Roland with Rousseau, she went to knock at his door, hoping for an interview. The note she handed at the door said:

I come to you as the oppressed come to Voltaire's. I am at your door, and I flatter myself that you will do me the honor to see me.' Beaumarchais' servant took the note to his master and came back with the response that Beaumarchais was busy and could not see her right now. Olympe asked for his at home day, so that she could come back when he was not busy, but was told that Beaumarchais could not be certain of when he would be free. Olympe left in a huff. Four months later, she published her account of the incident in the preface of the play. Unlike Manon Roland, she lacked the delicacy to make light of the incident. Le Mariage Inattendu de Cherubin remained unperformed, until she decided, later on, to take it and others (her reputation with the Theatre Français never quite recovered from Beaumarchais' assault) to the provincial theatres. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed