|

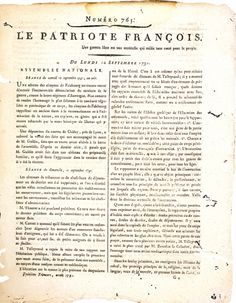

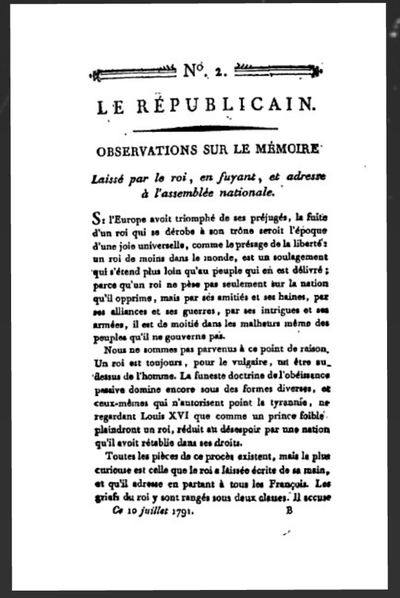

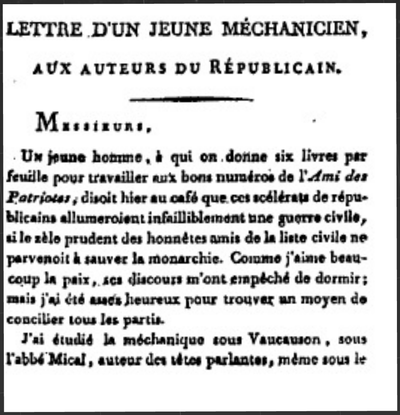

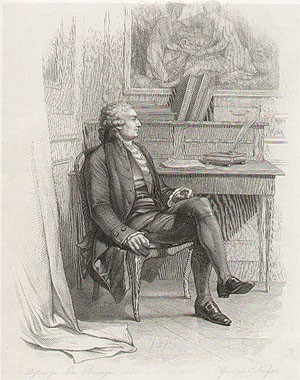

When Paine submitted his 'Letter' to his friends Brissot and Condorcet to publish as an advertisement for their new paper Le Républicain, it needed to be translated. Paine spoke and read French, but didn't like to write it. It had been decided, for some reason, that Achille Duchatellet, not Paine, would sign the article before it was pasted all over Paris, and published first, in Brissot's Patriote François, and then as the leading article of Le Républicain. Etienne Dumont, translator of of Jeremy Bentham, was approached first. Dumont refused, on the grounds that he did not want to be involved in what he saw as a foolhardy enterprise by 'an American and a young fool from the French aristocracy who put themselves forward to change the face of France' . The other member of the team who was able to translate was Sophie - hence, she probably got the job. But Sophie's participation in the journal did not end with translation. Two anonymous articles may be attributed to her. The first is very short. Entitled "Letter from a young mechanic" it proposes that the royal family and its entourage be replaced by a set of automaton. Even though such machines are expensive, they will cost a fraction of what the French people are spending on their actual king. And what's more, the mechanical king, far from being a tyrant, will raise its pen and sign everything its government wants it to! The second article is a long and very critical piece on the King and the mechanisms of his government. This article, it seems, was originally supposed to be written by Dumont, but he withdrew, when the king was returned to Paris. Dumont, however, had left a set of notes at the Condorcet. He later complained in his memoires:

There is good stylistic evidence that the person who 'rewrote' Dumont's piece was in fact Sophie. In particular, an image she uses in her Letters on Sympathy can be found in the article, that of the king (and monarchy) as a rattle designed to amuse the immature French people, to distract them from the fact that they are not free.

0 Comments

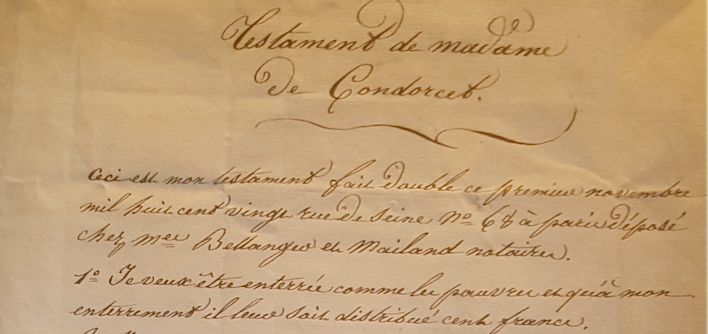

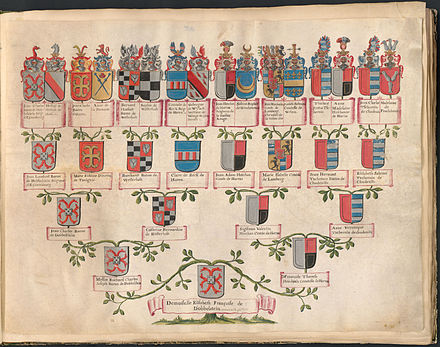

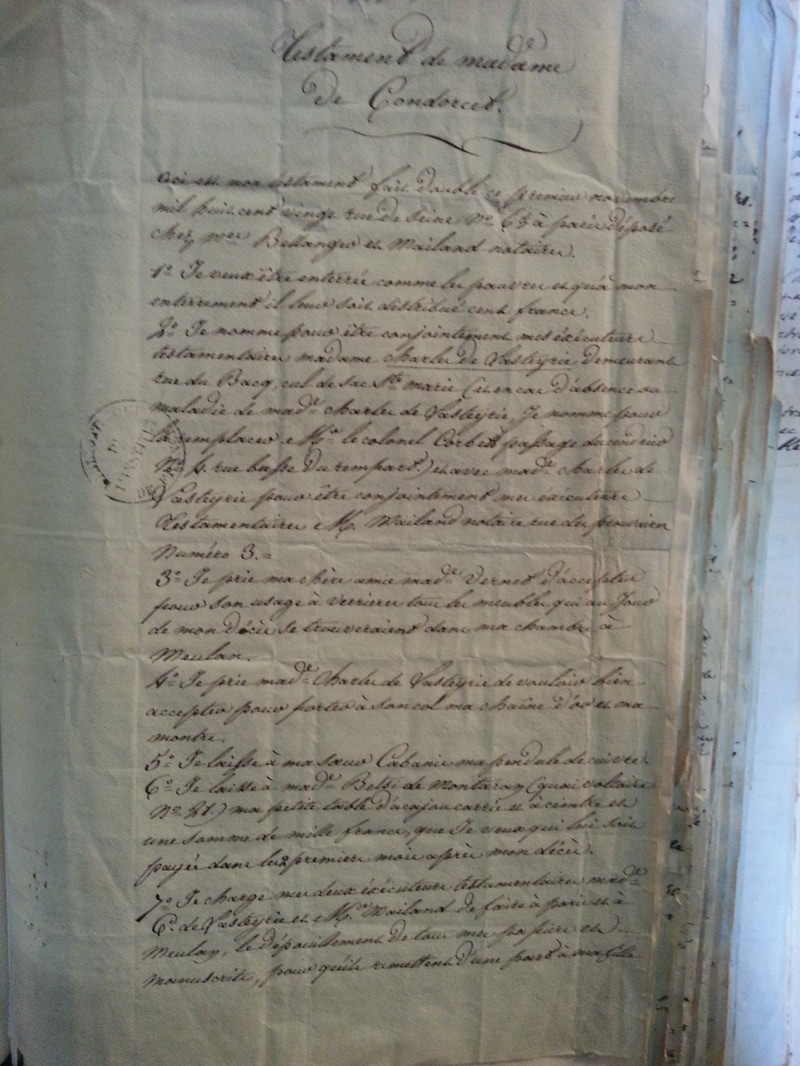

Paine remarked that the life of the French peasant before the revolution was nothing short of abject, and put paid to the Hobbesian theory that humans were always better off in the civil state than they would be in the state of nature. The revolution was, at least in principle, meant to redress some the most extreme instances of inequality. But the leaders of the revolution are often accused of not really having the best interest of the poor in mind. How would they know what the lives of the poor were like? What did an aristocrat like Sophie de Grouchy really know or care about the poor of France? As a child, with her mother, she visited them - an important part of her education was charitable visits. In her Letters on Sympathy, she thanks her mother for showing her the true value of such hands on charity: Yes, seeing your hands relieve both misery and illness, and the suffering eyes of the unfortunate turning to you, softening as they blessed you, I felt my heart become whole, and the true good of social life was made clear to me, and appeared to me in the happiness of loving and serving humanity There's something perhaps a bit distasteful about the very rich dispensing weekly, or even daily graces on the poor, when they could so easily relive most of their sufferings by relinquishing half their luxuries. Or perhaps this is politically or historically naive. In her Letters on Sympathy, Grouchy theorized her attitude to charity. Hands on charity is good, she says, not just because it relieves suffering, but because it teaches sympathy. Sympathy in turns becomes morality, and justice, and the desire to reform laws and social institutions so that extreme inequalities no longer exist. She does not want to erradicate all inequalities - some that are down to chance, or temperament, will survive. But there is enough good land in France, she says, to ensure that no-one be poor, even if three quarters of it goes to the rich, and the last quarter is divided amongst the common people. Photo of a copy of Sophie de Grouchy's will, held at the Bilbliothèque de l'Institut, courtesy of Millicent Churcher. Sophie saw her ties with the poor through to the end of her life. In her will she asked that instead of being buried at great expense in the family vault, she asked to be buried as a pauper, and that the money saved be distributed to the poor. When Sophie de Grouchy was young, no tutor was assigned to her. But she benefitted from her mother's instruction, a woman known for her intellect, culture and generosity. And she was allowed to participate in her younger brothers' lessons. She did so well at this that when their tutor was sick, she took over their Greek and Latin instruction. At the age of 18, she was sent to a finishing school in Normandy, at Neuville-les-Dames, near Macon, a secular convent for ladies. She received the title of Chanoinesse, and was addressed as Madame. In order to gain admission, one had to pay a substantial fee and maintenance amounting to 9000 pounds per year, but also provide proof of lineage: 9 generations on the father's side and 3 on the mother's. The convent was not ostentatiously religious. Pupils studied Latin and modern languages, and worked on their accomplishments. They hosted parties, the purpose of which was to find husbands of the right sort. In an environment that was religious and socially privileged, she became an atheist and socially aware. She discovered Voltaire and Rousseau, she read and translated Tasso's Jerusalem, and an unnamed work by Young (probably his Tour of Ireland). Her aunt, visiting her, worried about her health - her eyes were puffy every night and ached so that she feared it might be a form of gout. And yet Sophie kept on with her work.

The building Sophie lived in is long gone. But Neuville now has an Allee Sophie de Grouchy, on which stands an elementary school, l'école Condorcet. There are many schools named after Condorcet in France, but if this one is named after the Marquise, not the Marquis, then it is, as far as I know, unique. In 1798, Sophie de Grouchy published her Letters on Sympathy. We know that she already had a draft in 1791, which she'd sent to her friend Dumont for feedback that never came. We know that the Letters were complete in 1794, and that they had a title, as Condorcet refers his daughter to them in his Testament. So why were they only published in 98? We don't know as she did not leave an account. But it's likely the answer lies either in need, opportunity or both. After the Terror, Sophie needed money, and she decided to translate Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiment. Smith was very popular, and existing translations of this text were not particularly good, so there was a clear gap in the market. This also gave her the opportunity to publish her own short text. Her Letters were after all a critique and commentary of Smith. So she appended them to the translation. Although the Letters are in fact a more like a treatise than a record of correspondence (there is in fact only one letter writer involved), each chapter is set out as a letter to someone addressed as C***, announcing the topic of discussion, linking it to the previous one, and at the end, drawing out the conclusions to be taken forward to the next chapter. C*** is also an excuse for considering objections to Grouchy's arguments, with many paragraphs starting with formulas such as "No doubt you will tell me, my Dear C***". So C*** is very much a philosophical interlocutor, the Platonic touchstone to Sophie's Socrates. So who is C***? The obvious assumption is that it is Sophie's husband, Condorcet. But there are reasons why this is probably not true. First, her husband was dead by the time the Letters were prepared for publication. Secondly, if Sophie was to record a fake dialogue with a real person then she would probably have picked someone she actually corresponded with - in 1791, when the letter were written, Sophie and her husband were not apart long enough to correspond. But there were at least two more Cs in Sophie's life, to whom she was very close, with whom she did correspond and who were still alive when the Letters were published. They were her sister Charlotte, and Condorcet's close friend, Pierre George Cabanis. Of the two, C*** cannot be Charlotte, as 'My Dear C***' in French is 'Mon Cher C***' which is masculin. So Cabanis is more likely. Cabanis, as it happens, did correspond with Sophie on topics very close to her Letters, on Physiology, a materialist science aiming to understand human beings through their bodily organs. In 1802, Cabanis published his Rapports du Physique et du Moral de l'Homme, in which he explores the relations between bodies and morality, discussing for instance, the influence of weather and digestion on mood and decision making. Prior to publishing this, he corresponded with Sophie, and had long discussions with her on the subject.

Physiology is also central to the Letters on Sympathy, as Sophy argues that our moral feelings are born out of the physiological response that ties a newborn to the person that nurses her and holds her. Cabanis and Charlotte de Grouchy became lovers during the Revolution, and in 1796, they were married. Some readers like to see a love story behind every text (in particular, texts written by women!) but in this case, we must suppose that C*** was very much an intellectual interest (and a close family friend) but not a love interest. Cabanis was by profession a doctor in medicine but did not practice. Some say that was because of his own poor health. Some say that he was in fact a spy, not a doctor. He is also reputed to have given Condorcet a dose of poison to hide in a ring. And this poison, in some accounts of Condorcet's death, is what he took to kill himself when he was captured in March 1794. Janet Todd, Wollstonecraft's biographer, suggests that Wollstonecraft may have been contacted in 1792 by Condorcet and Paine to help rework the plan for educational reform that Talleyrand had started in 1791. Might Wollstonecraft have at least considered taking them up on the offer, and might she have met Condorcet's wife, Sophie de Grouchy over dinner? Probably not. When Wollstonecraft was in Paris, she mostly visited English nationals, such as Helen Maria Williams, and Johnson's associate, Thomas Christie. She was close, ideologically, to the Girondins, some of which were fluent English speakers. Brissot, for instance, had visited England, and developed a friendship there with Catharine Macaulay. Manon Roland also spoke English, having taught herself at the beginning of her marriage, and travelled to England, where she was much impressed with the cleanliness and simple habits of the inhabitants. Sophie de Grouchy was also a fluent English speaker and writer, so that her salon in the early years of the revolution attracted foreign luminaries such as Thomas Paine and Jefferson. But by the time Wollstonecraft moved to Paris, Sophie no longer had a salon, and Manon did not admit any woman in hers. It is therefore unlikely that they would have met. Had they read Wollstonecraft? Again there is no evidence. But a letter dated 20 August 1791 from Sophie to her friend Dumont suggests that perhaps she may have come across one of Wollstonecraft's books. Sophie thanks Dumont for sending her books and political news from England and says: "Until I receive more news from you, I will be busy reading the book you sent me and dreaming about the best way to raise reasonable women who can live with men who are not and will not be reasonable towards women for a long time from now". This could, of course, be coincidence. But it does suggest that the book Dumont sent her and Sophie's dreams might be related. And who, better than Wollstonecraft could be the inspiration for such dreams?

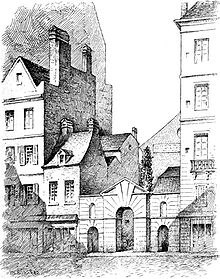

Just as Olympe de Gouges did, Sophie de Grouchy had to relocate to the suburbs during the Terror. In 1793, the Jacobin Chabot had issued an order to arrest her husband, Condorcet. Condorcet had gone into hiding in the house of Madame Vernet, on the Rue des Fossoyeurs (now the Rue Servandoni). Their property was confiscated by the government, and Sophie, together with her young daughter, her nanny and her sister Charlotte, moved to a house on the Grande Rue D'Auteuil, not far from where Madame Helvetius lived. Several times a week, Sophie walked into Paris to visit her husband. As she did not want to be recognised, or to attract anybody's attention to Condorcet's hiding place, she came dressed as a peasant woman, pretending to be with the crowds of farmers come to sell their goods to the starving capital. Once through the gates, she would lose herself in the crowds come to see that day's executions at the Place de la Revolution (now Place de la Concorde), then cross the river to reach the left bank, and walked towards the church of St Sulpice, and beyond that to the street where her husband was hiding. Often she would bring him books, or notes that he needed for his work - as he'd had to leave home in a hurry. She would also stay and encourage him, and work with him. His last work, the Sketch of human progress, was almost certainly something they worked on together. After seeing her husband, Sophie would walk back across the Seine towards the Rue St Honoré, where she rented an underwear shop and the half-floor above it. Putting Auguste Cardot, younger brother of her husband's secretary, in charge of the shop, she set up a studio in the alcove and worked on her miniatures from there. Thus she insured that she had sufficient income to see to the needs of her husband, her family and herself until she could claim back some of what the government had seized.

In the spring 1792, Sophie de Grouchy, Marquise de Condorcet wrote to her friend Etienne Dumont, speech writer for Mirabeau, and translator for Jeremy Bentham, sending him some of her manuscripts for feedback. "Here are the inchoate manuscripts I mentioned to M.Dumont, or rather the indecipherable sketches. I have lost the eighth letter on sympathy. As to the other mess, it contains as yet only a few weak traces of a development of character and passions, and that is not yet strengthened by any of the circumstances that make a novel interesting. One of the main causes of my laziness when it comes to working on it is 1) difficulty in obtaining good advice (will some arrive from overseas!) 2) the fear of not having the means of executing the ideas which, in other hands could enrich the subject matter, but in mine, will probably make it less. If M.Dumont were to dine here this Tuesday, I would be in a better position to take heed of his advice, but also, they might be more frank if they are in writing. There is no need, I know, to ask him to speak to no-one of that which I send him." Letter to Dumont, spring 1792. Apparently, Dumont did not reply, and either he did not come to dinner, or the conversation did not turn to Sophie's writings.

"You are a merciless man for poor authors, especially a for a shameful author like a woman. What would it have cost you to tell me whether what you'd seen from my drafts deserved to be developed? I give you my word you would have had no grief from it." 19 May 1792. Why did Dumont not reply? Perhaps, despite his friendship for Sophie, he was not entirely persuaded that women should waste their time in literary pursuits, or that their contributions would be particularly good. Or perhaps he did not wish to spend his leisure time doing for free what he did for a living! Fortunately, the Letters on Sympathy were already fully drafted, and six years later she published them, together with her translation of Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments. Unfortunately, we know nothing of the novel. Was she discouraged by Dumont's refusal to talk about it, and did she give in to the laziness she refers to in the first letter? Elizabeth Vigee le Brun, the famous portrait painter of the late eighteenth century, was married to a man who saw her art as his private source of income. Finding that what she earned from painting portraits was not enough, he decided that she ought to teach. She recorded her reaction in her memoirs: "I agreed to his request without taking the time to think about it, and soon, a number of young ladies came to me, to whom I shewed how to make eyes, and noses and ovals, which I had to correct all the time. This took me away from my work and was a tremendous bore". One of her students, according to Guillois, was Sophie de Grouchy. Her biographer doesn't say when she had these lessons, but looking at the dates when Vigee le Brun was teaching, it must have been during the early years of Sophie's marriage to Condorcet, before the Revolution, when the couple were living in the Hotel des Monnaies in Paris and Sophie was attending lectures at the Lyceum, a school for the public set up by Condorcet and La Harpe. Although Sophie may have been one of Vigee Le Brun's irritating students, having to have her eyes and noses redone by the master, she nonetheless became a very decent miniaturist herself. We have several of her self portraits (including one in the nude). Sophie was in fact such a successful miniaturist that during the Terror she supported herself, her daughter, sister and her nurse by going around the prisons of Paris and painting the portrait of prisoners for their families. On two occasions, Guillois tells us, she avoided arrest by drawing the soldiers come for her for free.

Looking through some documents, I came across a pastel miniature portrait of Manon Roland, drawn, apparently, at the Conciergerie. There is no signature, and I have not been able to trace any information about it. But doesn't it just look like one of Sophie's? In his testament to his daughter, Condorcet tells us that his wife, Sophie de Grouchy, as well as her Lettres sur la Sympathie, wrote other texts in moral philosophy.

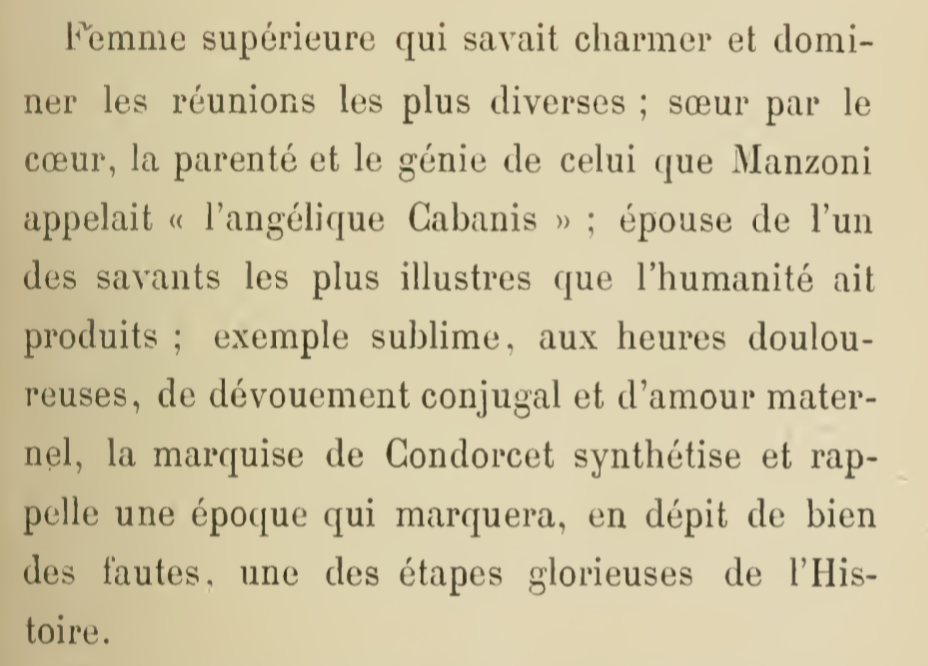

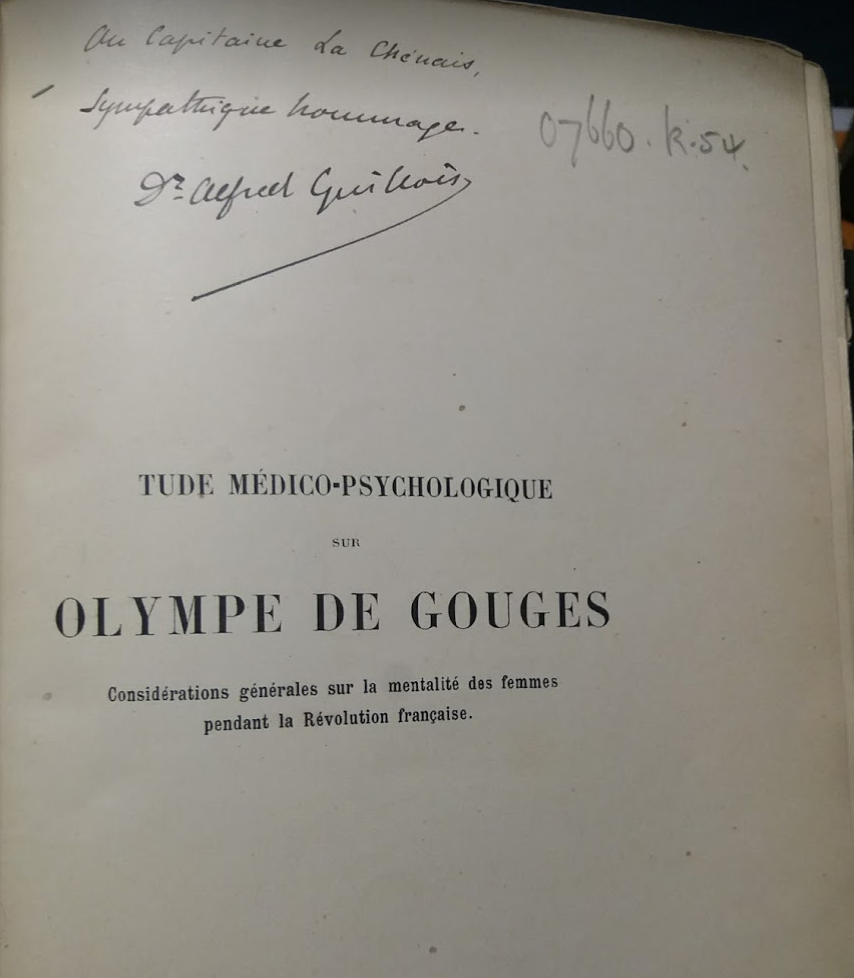

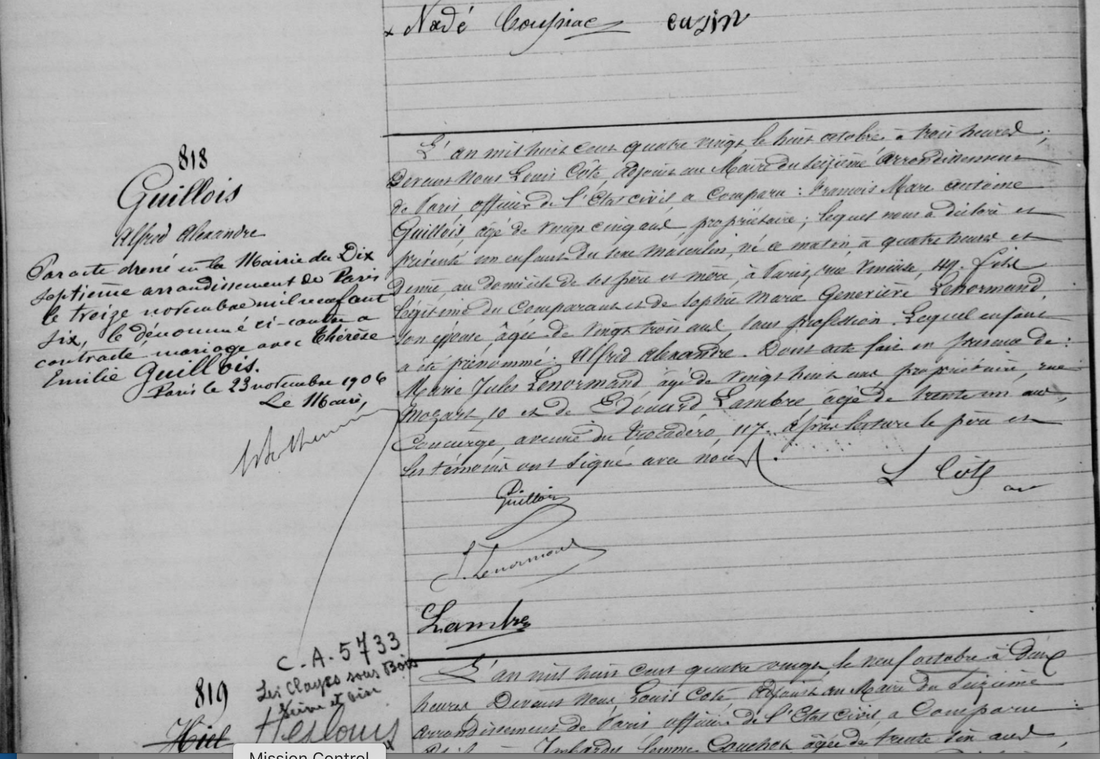

These are apparently lost, along with her manuscript of the Lettres. In the summer 2015 I visited the Bibliotheque de l'Institut in Paris, on the Quai de la Monnaie, where Condorcet and Grouchy used to live, and which houses all the papers related to the Academie Francaise. I was hoping to find some trace of her papers. I found her will, stating that she left her papers to her daughter, Eliza, and her sister, Charlotte Cabanis. Her executor was Madame de Lasteyrie, Lafayette's daughter. Next stop the Cabanis archives? Sophie de Grouchy's first biographer was the civil servant, part-time historian Antoine Guillois. His book, La Marquise de Condorcet, sa famille, son salon, ses amis, portrays Sophie as a 'superior woman' praised for her beauty, her virtue and her intellect. Guillois dedicates his work to Sophie's grand nephew, the Vicomte de Grouchy. Olympe de Gouges also had a biographer named Guillois, a young medical student who chose to write his thesis on women's psychology during the revolution, focusing on one case, a woman clearly suffering from paranoid delusions, according to his expert diagnostic. Would it be too much of a coincidence if the two Guillois were related? It's by no means an uncommon name. In fact, in my searches, I discovered some Guillois of that period based in Turkey! But as it turns out, they are father and son, and here's the evidence on Guillois Junior's birth certificate (courtesy of a Guillois descendant , Jacques le Normand.

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed