|

The French translation of Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman was published before she arrived in Paris in the winter 1792, and reviewed favourably in at least four reviews, including one, La Chronique de Paris, edited by Condorcet. The name of the translator is not noted anywhere in the translation. Isabelle Bour, in an article on the reception of Wollstonecraft in revolutionary France, suggests that it was a Girondin. The translation is a good one: it contains spelling mistakes rather than mistakes in translation, suggesting that it was done in a hurry by someone who knew English well. It is also annotated in a way that suggests familiarity with English culture and literature, and a desire to defend 'Papist' France against the allegations of a protestant writer, while at the same time poking fun at Wollstonecraft's old fashion religiosity. The translator seems thoroughly on board with Wollstonecraft's defence of women, until, that is, we reach a footnote to Chapter 11 (which mostly concerns education of women) where we get a peak at the translators's common-revolutionary-garden variety and insidious sexism: Here the author is talking about France. It is true that the Revolution is allowing us to pay attention to women who for too long were treated with superficial respect and deep contempt. We owe them a better education; because mothers are the first teachers that nature and society offers children. We owe them divorce, which only the tyranny of priests was able to take from them. A large number among them have proven that they were worthy of liberty; they only need to be enlightened. More enlightened, they will become more virtuous and happier. We owe them reparation for all the gothic crimes of feudality against them, for inheritance, etc.; for if nature seems to refuse them political rights, they have as many claims to civil rights as men. In a word, it is up to them to give the new regime the firmness it needs. Since the French nation has shaken off it yoke, we have heard much about a counter-revolution. Legislators! Don't deceive yourselves: if there is to be a counter-revolution, it will come from the influence of women. So let the constitution concern itself with them, what you do for them will not be lost. What you have deposited in the hands of the paterfamilias really belongs to them, as they will transmit it to the future generations. The translator is quite clear that women are not and should not be political rights holders, and that the main reason why we should grant them rights is that they are mothers to future citizens.

Although Wollstonecraft does emphasise the importance of the role of women as mothers in a republic, she by no means reduces their citizenship to that, indeed, takes pain to say that women need not marry nor have children, but that they still deserve to be treated as full citizens. The translator clearly accepts what Sieyes proposed in the draft of the Constitution, namely that women should be only passive citizen, i.e. enjoy civil, but not political rights.

0 Comments

In her Memoirs Manon Roland questions the idea that it is wrong that women should serve as their husband's official secretaries. It is natural that husband and wife should work together she says. It is better for a woman to use her skills and intelligence drafting political pamphlets and letters than intriguing in her salon. Unfortunately, the other Jacobins did think that Roland was intriguing in her salon as well as drafting documents, and that the documents she drafted she did so in secret. Marat called her study a 'boudoir', suggesting that it was the entrance to her private quarters, where she entertained male visitors. The boudoir (a sort of sitting/dressing room, sometimes with a writing desk) was a boundary between the public and the private domain. While a 'salon' was a room used for entertaining visitors, and was as such very public, especially in the home of politically active people, the boudoir was more private and could only receive personal and close friends. But is was not as private as the bedroom, where only family and lovers could be entertained. The Marquis de Sade exploited this ambiguity of the boudoir in one of his books – La Philosophie dans le boudoir (sometimes badly translated as Philosophy in the Bedroom), the boudoir being the place where we can both debate public ideas, and perform private acts.

Israel's Revolutionary Ideas (2014) uses the French Revolution to argue for his greater intellectual agenda which is to show the historical importance of the Enlightenment. Putting the radical ideals of the Enlightenment into practice, he argues, is what the French Revolution was mostly about. Certainly, he is not the only person to think so.

I picked the book hoping to find a narrative that I could use to develop my own understanding of the French Revolution, but also, because I was rather curious as to how he would refer to the women of the French Revolution. His previous books on the Enlightenment have been rather male heavy, with less discussion than one might have hoped, for instance, of Mary Wollstonecraft or Catharine Macaulay. Revolutionary Ideas is no exception: out of 167 names listed as the "Cast of Main Characters", only 8 are women. Some omissions are surprising: Pierre-Francois Robert is listed, but not Louise Keralio-Robert. In the book she is referred to as his collaborator on the Mercure National (p.123). It would be more accurate to say that he had been her collaborator, as it was Louise who started the journal (previously, Le Journal d'Etat et du Citoyen) and she was its editor-in-chief. Robert joined the journal later, and they eventually married. While there are a number of references to both Grouchy and Gouges, they are not particularly enlightening or accurate. Grouchy is referred to as a 'leading exponent of women's rights' but we have no real evidence that she was even interested in women's rights. She did not write about it under her own name – that we know – nor is she reported to have discussed it with anyone. She did, however, contribute in writing and in editing Le Républicain to the leading ideas and arguments of the Revolution. Israel adds her names to various others, including most other women's names (they are rarely mentioned as individuals), also oddly, to Desmoulins's on p.206, and to a list of people who were released from prison after the Terror (she never went!) on p. 582. Olympe de Gouges is referred to as an ex-prostitute ('high class courtisane', p.123), which she certainly was not. She did, as far as we know, have a few lovers over the course of her lifetime, but by that criteria, it's likely that most of the characters listed by Israel were also prostitutes! She also gets the usual treatment of being described as an emotional creature – she is in turns fiery (123), angry (122) and disgusted (400). Gouges is also referred to, several time, as a leading feminist, which she was; but although her other political writings and activities are referred to, it seems that Israel only considers her notable for her feminism, which means that, like Grouchy, the greatest part of her contributions to the ideas that shaped the Revolution are forgotten. Israel is a leading historian of ideas, and Revolutionary Ideas is a very recent book. The fact that it says so little about the women of the French Revolution shows that my project of writing about these women is a much-needed one. In 1792, the conflict between Brissot and Robespierre came to a head, and eventually, a group of people whom we now call the Girondins, left the Jacobin club. Robespierre attacked Brissot in his own journal, Le Defenseur de la Constitution (issue 3, p. 138), and along with Brissot, he criticized his circle of friends, several of whom had been made ministers, arguing that much of their decision-making happened 'behind closed doors' and that they were not, therefore, publically accountable as republican politicians ought to be. Behind closed doors also means inside people's homes. Robespierre was accusing the Girondins of conducting public business outside of the public sphere, and in the private, or domestic one, where women were allowed to talk, and expected to take part in the decision-making. That this was a consideration becomes clear if we read Robespierre's tirade against Jean-Marie Roland. During both of Roland's turns in the ministry, Manon Roland held meetings in their homes. This, for Robespierre, was highly questionable: His house is the rendez-vous of the intriguers who assemble regularly in order to manage the interest of this faction [the Gironde], and the systematic calumnies they direct against the patriots And indeed, later on in the text, as Robespierre unravels what he sees as the extent of Brissot's treachery, he finds that at the end of a 'labyrinth of intrigues', there is a 'female triumvirate' (140). The image of the triumvirate is itself powerful: it refers back to Cesar, Cassius and Pompei taking over the Senate, and eventually destroying the republic. The early days of the Revolution had seen a different triumvirate: Antoine Barnave, Adrien Duport and Alexandre Lameth, constitutional monarchists who eventually left the Jacobins to found their own clubs, the Feuillants. All Jacobins, including the Gironde, had been united in denouncing them. By claiming the existence of a Girondin female triumvirate Robespierre is doing two things. First, he is suggesting that like the Roman and Feuillant triumvirates, this one presents a serious risk to the republic. Secondly, by making it female, he places it 'behind closed doors', in the domestic sphere, and therefore hidden from citizens who might hold it publically accountable.

The identity of Robespierre's female triumvirate is unclear. Marisa Linton, in her excellent book Choosing the Terror, suggests that the three women are Manon Roland, Louise Keralio-Robert and Sophie de Grouchy. Her source is a footnote in a 1939 edition of Le Defenseur de la Constitution by Gustave Laurent. Gita May also names those three women (using the same source) in her 1964 De Jean-Jacques Rousseau a Manon Roland: Essai sur la Sensibilite Pre-romantique et Revolutionaire. But it's very unclear why Laurent gave these three names in the first place. Certainly Manon Roland must be one of the three, as Robespierre mentioned her salon just a few pages earlier. Sophie de Grouchy (Madame Condorcet) also is a likely candidate as Condorcet is very much a target of Robespierre in that article, and because he mentions secret meetings of the Girondin faction with Lafayette, who was a close personal friend of the Condorcets. I'm not clear why Louise Keralio-Robert should be the third woman. She was not a saloniere, but frequented the salon of her neighbours, the Petions, and she was closer to Robespierre than to the Rolands. Other possible candidates for the third member of the Triumvirate would be Germaine de Stael – Brissot did frequent her salon – or Madame Petion. If any one has information about the identity of this third woman, please contact me or leave a comment! While we continue to investigate the lives, deeds and works of the great women of the French Revolution, let's not forget that some of these women were married, and that their husbands sometimes also contributed to the political events of their times. This is not, sadly always the case, and sometimes, what we have are rather petty disputes between men who were not as good at their jobs or deserving of their honour as they might have been!

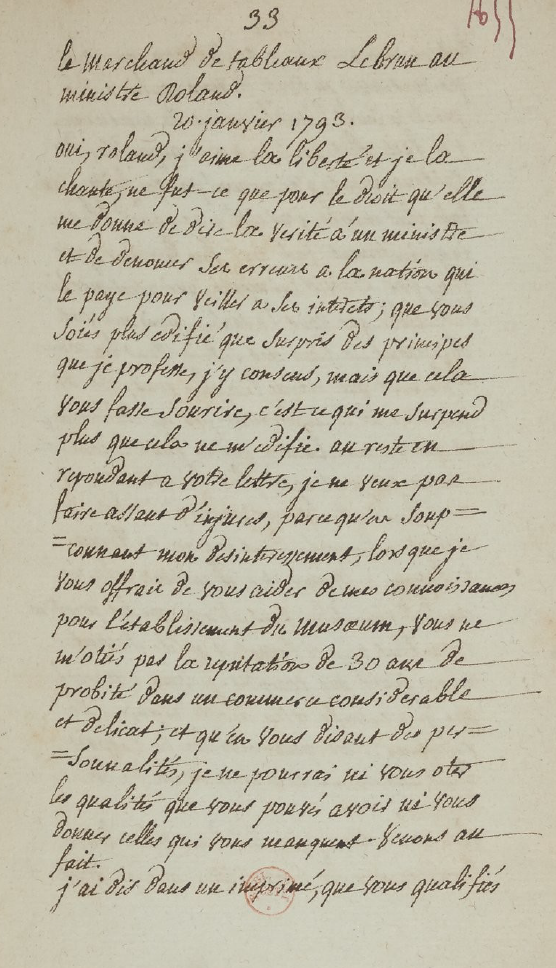

This is partly true of an exchange between Jean-Marie Roland, Manon's husband, and Charles Lebrun, husband to the celebrated painter Elizabeth Vigee-Lebrun. Lebrun was an ambitious art-dealer, supported entirely by his successful wife's earnings and works. However, Vigee Lebrun, who was Marie Antoinette's favorite portraitist, had gone into exile in the early days of the revolution. When she left, she took only 80 louis with her and left most of her fortune with her husband. While abroad she worked and continued to send her some of her substantial earnings to Charles. In order for that money not to be confiscated, Charles asked for a divorce – this was on paper only, and married life resumed as soon as she returned from her 12 year exile. Jean-Marie Roland was minister of the interior – but we know that a lot of his decisions were made by his wife, and that she wrote several influential letters for him. The two husbands came to fight over the question of how to look after the art confiscated from the aristocrats and the clergy. Lebrun thought he should be given the job and paid handsomely to do it. Roland thought this was not a priority. Lebrun published a pamphlet which Roland found insulting and even threatening, and Lebrun responded with an epistolary meltdown, accusing Roland of not being a true republican. I owe the details of this story to Bette W. Oliver's book, Surviving the French Revolution (chapter 4). Here is the first page of Lebrun's letter below, courtesy of Gallica When Manon Roland was at the prison of Sainte Pelagie, she found at first the company a bit too loud for her tastes: the prison was full of prostitutes and thieves whose ribald jokes she could hear through the thin walls of her cell. So when an old acquaintance Louise Petion was brought to Ste Pelagie, Manon was saddened, of course, but also relieved: she now had some company.

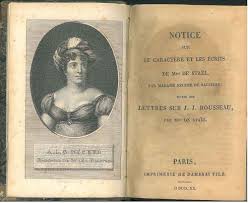

Unfortunately their friendship was tinged with tragedy. In September 1793, when she heard of the arrest of her daughter, Louise Catherine Angelique Ricard, veuve Lefevre, came to Paris to petition for her release. She was in turns arrested, and take to the Conciergerie. Almost immediately she was tried and condemned to the guillotine on the grounds of defending the re-establishment of monarchy. She is reputed to have claimed, when asking for her daughter's release, that Brissot and Petion and the proscribed Girondins were true republicans, and that if the French people wanted a king, they should have one. She was executed on 24 September 1793, at the age of 56, her daughter was still in Ste Pelagie. When Manon visited with her friend, she would have been dealing with the loss of her mother, but also been fearing for her husband. Jerome Petion had escaped with Buzot, Manon's lover (although the relationship was a secret, so Manon could not tell Louise that he was that). Petion and Buzot died together in a suicide pact. Their bodies were discovered in a forest, eaten by wolves. Louise-Anne Lefevre eventually came out of Ste Pelagie and, after the Terror, was granted a widow's pension. Her son, Jerome, lived on and pursued a military career under Napoleon. I was alerted by Eveline Groot, who gave a great talk this week at the Braga Colloquium on Women and the Canon, to yet another slight in the history of philosophy against a woman. This time, it's against Germaine de Stael, a writer who saw her share of slights in her life time, including some from Manon Roland and Sophie de Grouchy. But what Eveline Groot found is a 20th century historian of philosophy (or philology), who chooses to minimize the impact and import of Stael's philosophical commentary on Rousseau. Writing in 1915 in Modern Philology (13:7), G.A. Underwood claims that in her reading of Rousseau, Madame de Stael saw only the sentimentalist of the New Heloise, and not the rationalist of the On Social Contract, and that her Notice sur le Caractere et les Ecrits de J.J. Rousseau demonstrate 'little beyond an enthusiasm for Rousseau's ideas' (adding that the enthusiasm itself was significant'. Underwood concludes the introduction to his paper on Stael's interpretation of Rousseau by announcing that: 'The thesis will be that Rousseau leads Madame de Stael to become absorbed in her feelings'. The conclusion of the paper reads as follows: Such is the somewhat undeveloped Rousseauism of Madame de Stael when she began writing. It is an emphasis on temperamental inclination rather than a ripened criticism. A continuation of this study would show how in her mature and original work Madame de Stael gradually thought out to definite literary and philosophical tenets those ideas of Rousseau to which she was so strongly attracted. So one may well wonder why Underwood decided to write the article showing that in her early work, Stael was not a proper philosopher, but yet another female with inflamed emotions, rather than study the philosophical tenets he agrees she later came up with.

We can add G.A. Underwood to the list of scholars for whom, when it comes to the study of women philosophers, the important work to be done is to show how uninteresting and un-philosophical their work was. The Letters on Sympathy were published in 1798 as an appendix to Sophie de Grouchy's translation of the final edition of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and of On the Origins of Language. However, we have good evidence that the Letters on Sympathy were drafted earlier, in 1792 as she sent copies of them to her friend Etienne Dumont in the spring 1792, and her husband, Nicolas de Condorcet refers to them in his 1793 ‘Advice to his Daughter’. These may, however have been early drafts, and it is likely that Grouchy would have wanted to revise them somewhat before publication six years later. But did the Letters exist even before hand? Pierre Louis Roederer, idelogue and member of Grouchy's circle after the Revolution notes, in his Memoirs and in a review of the Letters published on 14 July 1798, the existence of an earlier manuscript which he had seen in the hands of Sieyes in 1789 or 1790. Although it's possible that a draft existed then, the fact that Roederer himself cannot remember the exact date (1789, or 1790?), that his testimony occurs nine years after the fact (and they were a busy nine years!) and that we have a dated letter from Grouchy to Dumont about her writing the manuscript, 1792 is a more reliable date. Roederer, although he mostly praises the Letters in his review does have some criticism. She ought not, he says, to have addressed the Letters to Condorcet and taken the tone of an instructor, as Condorcet would already have known and understood everything she could possibly write! (But in fact, we have good reasons to think that the C*** of the Letters was Cabanis, not Condorcet). On the other hand, Roederer does not accept another criticism, namely that Grouchy's style lacks the gracefulness of a woman's writing or the authority of a man's. Her style, he says, is adapted to her subject. He points out that sentiment and frivolity is not conducive to a clear discussion of thorny subjects. Madame du Chatelet, he adds, did not write her Physics using the stylistic 'tricks' of Madame de Sévigné, and Sévigné herself did not use these 'tricks' when she wrote about human understanding and moral sentiments. He concludes that Grouchy's style, although not always 'pure' is clear, simple and without pretensions.

In a 1790 text addressed to Necker, when he is about to leave France to go into exile, Olympe de Gouges announces that she too is ready to leave France. She has done her best, but that was not enough, and she now has too many enemies to stay safely. But her message is also to the French: unless you change your way fast, she says, you will lose your revolution, and your liberty, and you will find that you are better off with a king. She goes on to tell him the following story: a coach driver insulted a national guard. When Olympe challenged him, he said that the national guards treat people like him badly, that they don't pay, and that he and his family are starving despite his work. He concludes: I were a good democrat when the Revolution started, because I thought I would get something out of it. But now, I'm aristocratic as a dog Olympe reflects sadly on this state of things, and judges that democracy has not yet taken hold in the French and that they may not be ready for it: The counter-revolution will happen by itself, through the force of nature, especially if the French go another six months at this present rate. Things are destroyed, nothing is built. Everyone wants to be in charge, no-one wants to obey. All is reduced to nothing, everything is in a terrible disorder. The love of liberty still turns French heads, but once it is gone, they will recognize, I hope, that one master is better for them, than all men being masters at once. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed