|

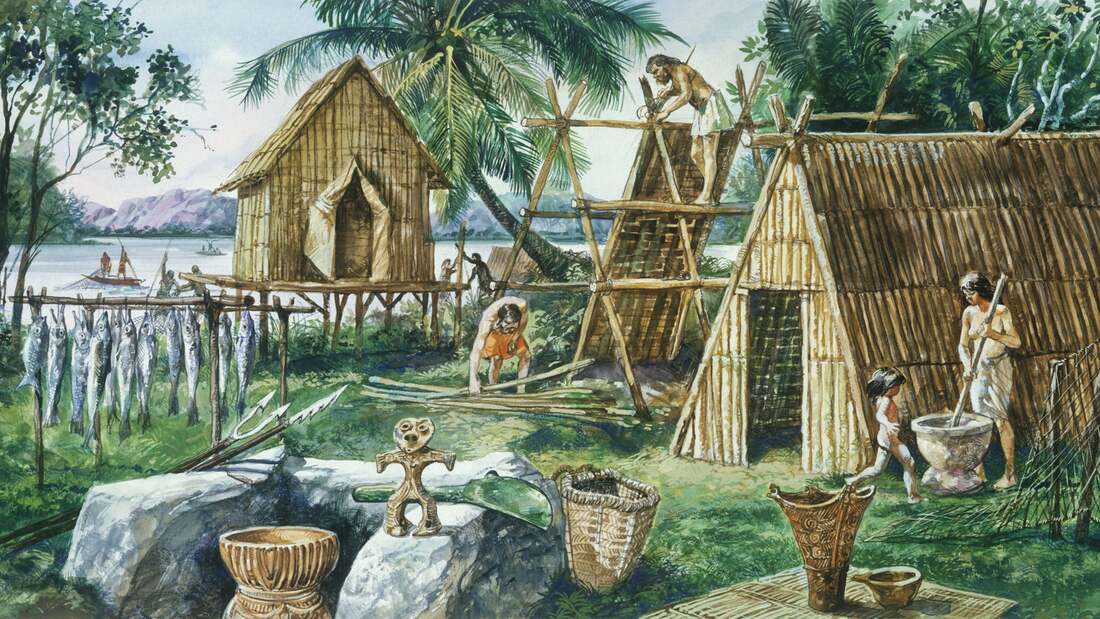

I read a book this week which got some-things-wrong about the history of the division of the spheres. I reacted by adding angry little notes in the margin, then by questioning the judgment of the press that printed it. After that I reflected that the percentage of the things that the book got wrong, compared to the vast quantity of demonstrated expertise by the author on the main topic of their book was really minimal. (Also the same press once published something of mine and I’m pretty sure the mistakes I made in that book were greater as well as more numerous and irritated a great many readers). So why did I care at all, beyond the fact that I’m currently writing a book about women philosophers and domesticity? Because I think it matters that we get our history right. Most people don’t’. Even Simone de Beauvoir floundered: “This world has always belonged to males, and none of the reasons given for this have ever seemed sufficient. By reviewing prehistoric and ethnographic data in the light of existentialist philosophy, we can understand how the hierarchy of the sexes came to be. We have already posited that when two human categories find themselves face- to-face, each one wants to impose its sovereignty on the other; if both hold to this claim equally, a reciprocal relationship is created, either hostile or friendly, but always tense. If one of the two has an advantage over the other, that one prevails and works to maintain the relationship by oppression. It is thus understandable that man might have had the will to dominate woman: but what advantage enabled him to accomplish this will?” The Second Sex, Book I, part 2, ch.1. The prehistoric and ethnographic data Beauvoir mentions pretty much repeat what the State-of-Nature theorists of the Enlightenment were saying: it was the advent of agriculture and the settlement of family groups that came with it which brought about women’s subordination. Rousseau says it, Condorcet says it, and modern science says it. Except that it doesn’t any more. It turns out that prehistoric data shows no such thing, and that the evolution of human tribes from hunter-gathers to agricultural villages to national states is a bit of a myth. That’s what Graeber and Wengrow showed when they reviewed extensive recent scientific findings for their book The Dawn of Everything. Human history (and prehistory) is way more complicated and way more interesting, and it’s impossible to pinpoint a time or a place when injustice or the oppression of a particular class set in. Injustice and oppression, it turns out, come and go as much as much as anything else. They are not necessary features of human existence.

We probably shouldn’t be surprised at such debunking: why would science conveniently agree with the stories imagined by 18th century philosophers? That’s got to have raised serious alarm bells with anyone not interested in maintaining the gendered hierarchical status quo. Except it didn’t. We are far too ready to trust learned men. Or women: hence my slightly over-the-top irritation when I read the book-with-the-mistakes. It matters that we don’t tell tall tales about why women so often end up in the kitchen instead of in political office. The reasons are complex, and their histories reflect many twists and turns which show how things may have gone differently, and how they did go differently sometimes, and how women themselves were actors in their destinies and not just victims of historical shifts. That’s why in my book (work-in-progress, nearly done!) I take care to look at many periods, many places, and many women. There isn’t one history of domesticity, one reason why we have the double-shift, or why women who iron their husband’s shirts don’t get paid for it. There are many reasons, many historical prompts, and therefore, many ways to fight back. That being said, I also anticipate that readers will find many mistakes in my book. I’m a philosopher tackling history, so that’s bound to happen. But among these many mistakes, I sincerely hope they’ll also find a way to make sense of their own domestic situation.

1 Comment

Catharine Beecher was a proponent of the cult of ‘True Womanhood’. Women, she believed, derived power specifically from domesticity, so that there was no need for political action. She therefore disagreed strongly with Angelina Grimke’s call to women to mobilize against slavery, and in her response to Grimke, An Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism (1837), she wrote: Woman is to win every thing by peace and love; by making herself so much respected, esteemed and loved, that to yield to her opinions and to gratify her wishes, will be the free-will offering of the heart. The kind of direct political action Grimke recommended - petitioning Congress - could jeopardize the influence that women had already achieved and any future progress they might make. To illustrate what she saw as the inherent wrongness of Grimke’s abolitionist writings, she cited the example of another woman writer and activist, Frances Wright. Frances Wright, a Scottish philosopher who emigrated to America and attempted experiments to abolish slavery and extend republican rights to women went counter to everything Beecher believed in. Not only does she step out into the public sphere, but she stands on a stage: ‘If the female advocate chooses to come upon a stage, and expose her person, her dress, and elocution to public criticism, it is right to express disgust at whatever is offensive and indecorous, as it is to criticize the book of an author.’ (Essay on Slavery, 121) Beecher had previously expanded on what see found ‘offensive and indecorous’ in Wright’s public appearances in her Letters on the Difficulty of Religion (1836). The ‘appropriate character of a woman’ she says, ‘demands delicacy of appearance and manners, refinement of sentiment, gentleness of speech, modesty in feeling and action, a shrinking from notoriety and public gaze, a love of dependence, and protection, aversion to all that is coarse and rued, and an instinctive abhorrence of all that tends to indelicacy and impurity, either in principles or actions.’ (22) Fanny Wright fails on all these counts, because of her looks, her demeanour and her actions: ‘with her great masculine person, her loud voice, her untasteful attire, going about unprotected, and feeling no need of protection, mingling with men in stormy debate, and standing up with bare-faced impudence, to lecture to a public assembly. And what are the topics of her discourse, that in some cases may be a palliation for such indecorum? Nothing better than broad attacks on all those principles that protect the purity, the dignity, and the safety of her sex. There she stands, with brazen front and brawny arms, attacking the safeguards of all that is venerable and sacred in religion, all that is safe and wise in law, all that is pure and lovely in domestic virtue.’ (23). Beecher was very invested in arguing for women’s domestic power - to the extent where one feels that for her, a good housewife could manipulate the world of politics from afar, righting wrongs without stepping out of her sphere. Part of her investment was educational. She taught, she started her own school, and she defended in writing (white) women’s right to education, and argued that domestic science ought to be taught properly, so that women would not suffer or cause others to suffer when put in charge of a family’s welfare.

To be a woman, for Beecher, came to mean being an expert in domestic science, a keeper of health, morals, safety and general well-being. But in these earlier writings, it also means looking a certain way. Part of what is wrong with Fanny Wright is that she is physically, mentally and emotionally not fragile enough. She can stand up for herself, and does not need to ‘lean on an arm of flesh, to sit as a doll […] to be admired for her personal charms’ (Angelina Grimke, Letter to Catharine Beecher XII, 2 October 1837). Fanny Wright looks too manly, she holds herself too straight, her muscles are too big, too apparent. She is crossing a visible line between femininity and masculinity, one meant to safeguard the distinctions of the spheres: for after, all, why would a woman who ‘feels no need of protection’ stay inside her home? Lucrezia Marinella, Venetian 17th century philosopher, wrote lives of saints, romances, and a famous contribution to the Querelle de Femmes in which she defended women’s superiority to men, turning some of Aristotles’ arguments on their heads: The Nobility and Excellence of Women, and the Vices and Defects of Men (1601). Women, she said, should work to develop their intellect, naturally superior to men’s, and to do so, they should not be confined to the home. Then, at the age of 74, she apparently recanted all this in a final book, Exhortations to Women and Others if they Please (1645), claiming that “A woman’s reputation must not leave the walls of her home”. Women, she seems to argue, this time following Aristotle, ought not to pursue an intellectual life, but should focus on the domestic arts and virtues. This is what they are naturally suited for, and what will make them, and their husbands, happiest. What happened there? Did Marinella simply become more conservative as she grew older, denying younger generations of women what she had taken for herself? That’s possible, but before we demote Marinella from the ranks of feminist heroine to those Boomerdom, let’s consider other possibilities. First, let’s look at what the Exhortations have to say about domestic work, its value, and whom it is good for. Marinella’s spin on Aristotle |

AboutThis is where I blog about my new book project (under contract with OUP): a history of the philosophy of the home and domesticity, from the perspective of women philosophers. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed