|

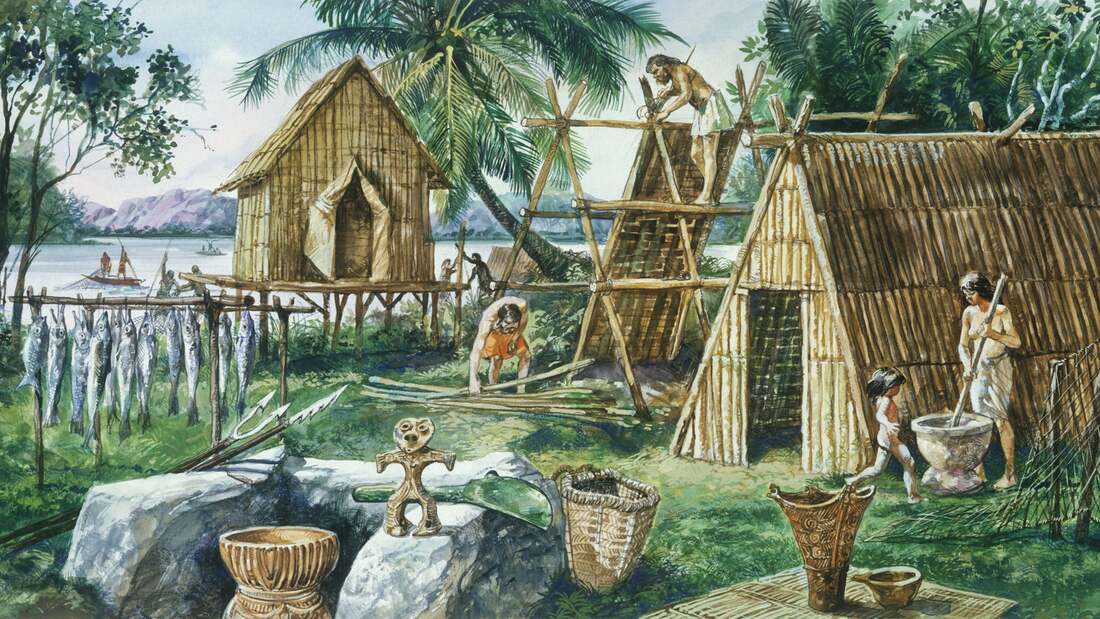

I read a book this week which got some-things-wrong about the history of the division of the spheres. I reacted by adding angry little notes in the margin, then by questioning the judgment of the press that printed it. After that I reflected that the percentage of the things that the book got wrong, compared to the vast quantity of demonstrated expertise by the author on the main topic of their book was really minimal. (Also the same press once published something of mine and I’m pretty sure the mistakes I made in that book were greater as well as more numerous and irritated a great many readers). So why did I care at all, beyond the fact that I’m currently writing a book about women philosophers and domesticity? Because I think it matters that we get our history right. Most people don’t’. Even Simone de Beauvoir floundered: “This world has always belonged to males, and none of the reasons given for this have ever seemed sufficient. By reviewing prehistoric and ethnographic data in the light of existentialist philosophy, we can understand how the hierarchy of the sexes came to be. We have already posited that when two human categories find themselves face- to-face, each one wants to impose its sovereignty on the other; if both hold to this claim equally, a reciprocal relationship is created, either hostile or friendly, but always tense. If one of the two has an advantage over the other, that one prevails and works to maintain the relationship by oppression. It is thus understandable that man might have had the will to dominate woman: but what advantage enabled him to accomplish this will?” The Second Sex, Book I, part 2, ch.1. The prehistoric and ethnographic data Beauvoir mentions pretty much repeat what the State-of-Nature theorists of the Enlightenment were saying: it was the advent of agriculture and the settlement of family groups that came with it which brought about women’s subordination. Rousseau says it, Condorcet says it, and modern science says it. Except that it doesn’t any more. It turns out that prehistoric data shows no such thing, and that the evolution of human tribes from hunter-gathers to agricultural villages to national states is a bit of a myth. That’s what Graeber and Wengrow showed when they reviewed extensive recent scientific findings for their book The Dawn of Everything. Human history (and prehistory) is way more complicated and way more interesting, and it’s impossible to pinpoint a time or a place when injustice or the oppression of a particular class set in. Injustice and oppression, it turns out, come and go as much as much as anything else. They are not necessary features of human existence.

We probably shouldn’t be surprised at such debunking: why would science conveniently agree with the stories imagined by 18th century philosophers? That’s got to have raised serious alarm bells with anyone not interested in maintaining the gendered hierarchical status quo. Except it didn’t. We are far too ready to trust learned men. Or women: hence my slightly over-the-top irritation when I read the book-with-the-mistakes. It matters that we don’t tell tall tales about why women so often end up in the kitchen instead of in political office. The reasons are complex, and their histories reflect many twists and turns which show how things may have gone differently, and how they did go differently sometimes, and how women themselves were actors in their destinies and not just victims of historical shifts. That’s why in my book (work-in-progress, nearly done!) I take care to look at many periods, many places, and many women. There isn’t one history of domesticity, one reason why we have the double-shift, or why women who iron their husband’s shirts don’t get paid for it. There are many reasons, many historical prompts, and therefore, many ways to fight back. That being said, I also anticipate that readers will find many mistakes in my book. I’m a philosopher tackling history, so that’s bound to happen. But among these many mistakes, I sincerely hope they’ll also find a way to make sense of their own domestic situation.

1 Comment

Stephanie Palmer

3/7/2024 10:26:13 am

I always try to stress to students that the cult of domesticity was a historical phenomenon, that grew at one period of history and waned at another. That women did not always 'stay at home'. They rarely get it. Your book will be welcome.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AboutThis is where I blog about my new book project (under contract with OUP): a history of the philosophy of the home and domesticity, from the perspective of women philosophers. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed