The best woman is she about whom there is least talk - for better or for worse. So said Pericles, in his funerary oration, when he was attempting to comfort the Athenians grieving for their dead (Thucydides II45). It is ironical that Plato, in Menexenus (236a), claims that the speech in question had been written by Pericles's mistress, Aspasia of Miletus. But since when is it a requirement that we hold men to consistency when they talk about women? One housewife who did not pay heed to Pericles’s injunction was Xanthippe, Socrates’ younger second wife. Xanthippe is ‘known’ to Socrates’ disciples, Plato tells us in Phaedo (66b), even to those who come from distant foreign cities.[1] This means that she had a bit of a reputation, and certainly, we find plenty of anecdotes about her in the ancient gossip literature. She is reported as having thrown water on her husband (‘I knew that after her thunder, rain would come’, he apparently remarked), chased after him in the market place and torn his coat off him. His friends thought her a shrew and asked why he tolerated her. The answer was ‘Because she is my wife and the mother of my children’. Xanthippe had plenty of reasons to be angry, of course, expected as she was to run Socrates’ home and bring up his children, without any financial security – as he was not working – and to cater for his rich friends, at a moment notice, with only cheap fare to offer them. As to her reputation, one must consider that she had very little to protect. A wive’s reputation was a husband’s guarantee for social standing. But Socrates’s own place in society was far too unusual to require that his wife be anything other than she wished or could be. So he had not interest in ‘training’ her to be a proper housewife, and no reason to make her homelife more satisfactory or easier for her. Xanthippe, was probably, as other women have been since, the victim of her husband’s ill thought-out ideology: her life was not regulated by the sort of superficial social mores Socrates disliked, but nor was it an examined life, as she was still expected to make sure food was on the table, and that the children were washed and fed. She might have been less angry had she been instead encouraged to follow Socrates around the market place, asking and answering questions. Xanthippe's life may have been not unlike that of Abby May Alcott’s (the mother of novelist Louisa May) whose transcendentalist husband took his family to live in a commune called Fruitland. During this failed Utopic experiment, the women worked day and night to make sure the philosophers did not starve, without any access to the usual tools and goods that would make that task easier. Abby May and her daughters, much like Xanthippe, were living the applied philosophy of the men, but without any help in implementing the principles, and under the blind assumption that the principles had to be right, and should not be questioned by failure. [1] Arlene Saxonhouse, 2018 “Xanthippe: Shrew or Muse” Hypatia, 33(4): 610-635, 617

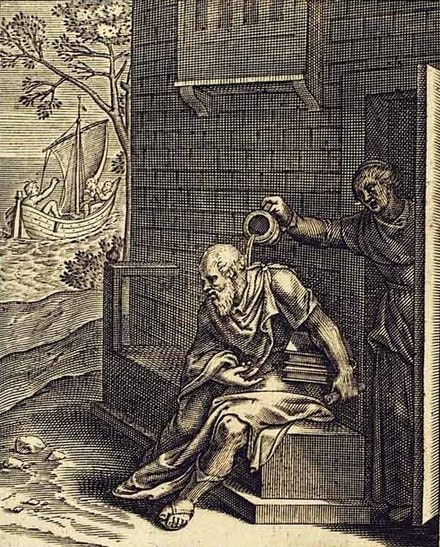

1 Comment

|

AboutThis is where I blog about my new book project (under contract with OUP): a history of the philosophy of the home and domesticity, from the perspective of women philosophers. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed