|

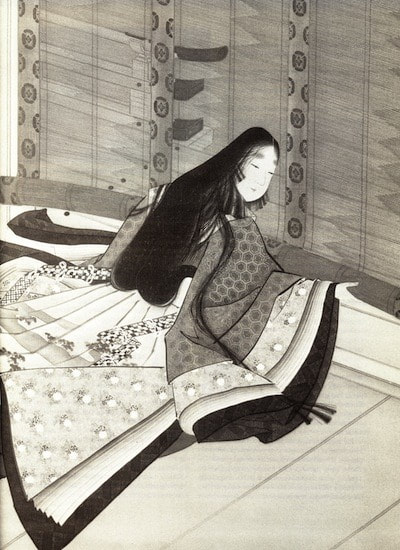

“If Aristotle had cooked” said seventeenth century philosopher and poet Sor Juana de la Cruz, “he would have written more philosophy”. In her experience, standing in the little kitchen adjoining her convent room, experimenting with eggs was the most fruitful way of studying matter and causation. Less neat, perhaps, than Hume’s billiard balls, but richer in the conclusions that could be drawn. But even cookery is a bit more glamourous than something men tend to steer clear of (as a topic for philosophizing, and often as an activity), which is plain cleaning and tidying: dusting, hoovering, folding and putting away laundry. Women philosophers, however, sometimes address it. Simone de Beauvoir famously dismissed housework as unrewarding and soul-crushing, something that only women who are victims of ‘bad faith’ can pretend to enjoy: Few tasks are more similar to the torment of Sisyphus than those of the housewife; day after day, one must wash dishes, dust furniture, mend clothes that will be dirty, dusty, and torn again. The housewife wears herself out running on the spot; she does nothing; she only perpetuates the present; she never gains the sense that she is conquering a positive Good, but struggles indefinitely against Evil. It is a struggle that begins again every day. The Second Sex, 539. Beauvoir was not the first woman philosopher to reject the life of housewifery. Sei Shonagon, fashionable lady-in-waiting for Empress Sadako, in 10th-century Japan, and author of the Pillow book, a collection of memories, anecdotes, lists, and philosophical reflections, also had little time for tidiness. “I greatly dislike a woman’s house when it is clear that she has scurried about with a knowing look on her face, arranging everything just as it should be, and when the gate is kept tightly shut” (tr. Ivan Morris, 1967, p.182) A (single) woman’s house she said, should instead be ‘extremely dilapidated, the mud wall should be falling to pieces, and if there is a pond, it should be overgrown with water-plants. It is not essential that the garden be covered with sage brush, but weeds should be growing through the sand in patches, for this gives the place a poignantly desolate look’. It is hard for a twenty-first century reader who is not acquainted with 10th century Japanese culture to figure out what is meant exactly in this passage. Is there a particular significance to an overgrown pound, or sage brush? It is tempting to say that the lack of attention to the building and the garden signals the absence of a man in the house, and perhaps works as an advertisement, or makes a show of helplessness, which will attract a potential husband, make him feel needed. Or maybe not – Sei Shonagon does not say, nor does she speak anywhere of the desirability of marriage. What this passage has in common with the rest of Sei Shonagon’s book, is a strong sense of what is aesthetically pleasing or not which goes beyond the sensory realm and into ethics. Being the kind of woman who scurries about making everything neat is not aesthetically pleasing. But this also relates more deeply to a sense of the good life. A life concerned with neatness and tidiness is not a life worth living: it is a closed life, one that excludes interesting interactions with others of the kind that will enrich us. It is closed in a very literal sense: the gate is ‘tightly shut’. In the following text, she takes up this theme again. It is good, she says, for a woman to stay with her parents when she is away from the palace. That way she will benefit from a lively household with comings and goings and will not worry about receiving her own visitors. Yet, the parents may be mean-minded in the way that the neat woman was: they sometimes spy on visitors, ask when they are living, and make a fuss about closing the gate at night. What Sei Shonagon wants instead is: ‘a house where no one cares about the gate either in the middle of the night or at dawn, and where one is free to meet one’s visitor, whether he be an imperial Prince or a gentleman from the palace. In the winter one can stay awake together all night with the lattices wide open. When the time comes for him to leave, one has the pleasure of watching him playing upon his flute as he goes; if a bright moon is still hanging in the sky, it is a particular delight. After he has disappeared, one does not go to bed at once, but stays up, discussing the visitor with one’s companions, and exchanging poems; then gradually one falls asleep.’ (Morris 184). So the good life, the one she ‘really likes’ is that where the time of day is of no concern, and details will not interfere with love, friendship and poetry. The woman who leaves alone, who does benefit from a busy household where people come and go, must at least show that she is poetically inclined, by leaving her gate open, and not caring overmuch about neatness and tidiness. Sei Shonagon’s dislike of the domestic virtues brings to mind Simone de Beauvoir’s description of the diligent housewife as a masochist, because she is engaged in a Manichean fight against dirt and mess which she is bound to lose: the dust will always come back, the food will always need replenishing and the dishes will always get dirty. Beauvoir’s own answer to this problem was to choose to live in a hotel: no cooking, no cleaning, and infinite disregard for her surroundings: they are someone else’s responsibility and to her, only a place where she sleeps and receives lovers. In a hotel, as in the ideal house Sei Shonagon tells us about, the door is always open, and questions are rarely asked. If Sei Shonagon is not a household name, Marie Kondo definitely is. Her books, her Netflix series, her shop, even, made her rich and famous. Her method for tidying (the KonMari method) has meant that millions of people who were happily folding their clothes in their drawers or shelves are now rolling them up, and lining them by colour, hoping they don’t collapse into a messy pile of shirts or a nest of unpaired socks. Marie Kondo doesn’t just want us to be neat. She asks us to engage with our surrounding, not scurry along, but stop in one place, get everything out into a pile, sort it, then arrange it according to category, function, colour, etc. It’s an emotional engagement: we need to ask ourselves whether a particular item ‘gives us joy’. This has received a lot of criticism: not everything we must keep gives us joy. The stick I use to walk because of arthritis does not give me joy. But do I want to get rid of it? No, because then the quantity of joy in my life will be even smaller, there will be more pain and less movement. But maybe, if I focus on the stick long enough, if I reflect on my reaction to it, I will realise that it is not the stick’s purpose to bring me joy, but to enable me to continue living my life as fully as possible until I can receive surgery. I am grateful to my stick for this. And if there is something that bothers me, it’s that I have been a bit slow about doing the things I need to do for surgery to happen. This is a useful thought, and one that’s brought about by considering Marie Kondo’s question mindfully: does that stick bring me joy? Ruth Ozeki, buddhist nun, journalist and novelist, brought her own take to the KonMari method in her latest novel, The Book of Emptiness and Forgetting. Tidying, cleaning, are a way of engaging with the world fully. Perhaps Ruth Ozeki’s take on Kondo may help us address Simone de Beauvoir’s worry: a housewife, who cleans the living room carpet day in, day out, but rarely dirties it herself because she does not leave the home, or when she does, she is never so fully taken up by her activities that she would forget to take off her shoes on coming home, is not in a position to engage with the world. She is not in the world. Or if she is, it is not as herself, but an accessory, a domestic robot, whose sole function it is to facilitate others’ being in the world. Calmly waxing the floor, even with a Mr. Miyagi ‘wax-on wax-off’ movement, will not teach her how to be a better person, or how to respect herself and her environment, because she is prevented from having the sort of free interaction with the world where questions of respect arise. Simone de Beauvoir may well be right about the futility of the fifties’ housewife’s life. But not about housework itself. Women often say that they would enjoy coming home from work early to spend the time looking after their home. Is this a flashback to earlier oppression, a sign that we are unable to let go of the roles that were imposed on our foremothers? Or is it the sign that at least some people (mostly women still) are finding that quiet focus on their immediate surroundings is actually a good way of being in the world? This is an edited version of a text published earlier on the Blog of the APA.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AboutThis is where I blog about my new book project (under contract with OUP): a history of the philosophy of the home and domesticity, from the perspective of women philosophers. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed