|

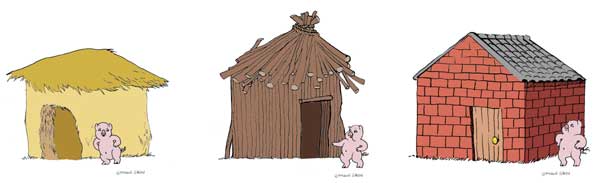

What does philosophy have to contribute to the understanding of 'home'? Analytic philosophy is in the business of conceptual analysis, finding the necessary and sufficient conditions for something to be what it is. Plato started it with his questions about the forms: 'What is Justice?' 'What is Beauty?' etc. Descartes pursued it from his armchair by the fire, asking 'What am I?', and philosophers have been chasing concepts with definitions ever since. A conceptual analysis attempts to capture a set of intuitions we have about a concept, so that once we come up with a definition, every instance of that concept and nothing else falls under it. So for instance, armchairs cannot be defined as 'comfy seats' because there are things that are comfortable to seat on which are not armchairs, such as sofas. So is an armchair a comfy seat for one person? Perhaps, but a good conceptual analysis would look for armchairs that don't fulfill the conditions of 'comfy' or 'seat', and for things that do that aren't armchairs before settling on that definition. Can we use appeal to the tools of conceptual analysis to help define the home? Attempting to capture the home in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions is a task that, if not doomed to failure, turns out to be singularly unproductive. Although most of us agree on the basic intuition that we need homes, these homes tend to look different according to what needs they serve, and that varies a great deal according to places and times. A home may or may not be a dwelling, something physical or not, that ties a family together, or a community, it may or may not involve property and land. This leaves room for plural definitions, perhaps definitions that succeed in capturing a certain 'family resemblance' in uses of the word across time and space. The idea that instances of a concept sometimes shared a 'family resemblance' rather than a set of necessary and sufficient conditions comes from Wittgenstein, who, when he attempted to say what a game was, found that some games had very little in common with others (say bouncing a ball against a wall, and D&D). He concluded that games, though definitely belonging to one concept, were not tied together by a set of necessary and sufficient conditions: I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than "family resemblances"; for the various resemblances between members of a family: build, features, colour of eyes, gait, temperament, etc. etc. overlap and criss-cross in the same way. – And I shall say: "games" form a family. Morris Weitz applied the Wittgensteinian idea of family resemblance to the concept of art, after noticing that it was impossible to bring all the things that we count as instances of that concept under a set of necessary and sufficient conditions. A definition of art would have to accommodate that have as little in common as a Greek tragedy and an 18thcentury piece of furniture. (Weitz, Morris (1956). "The Role of Theory in Aesthetics". Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 15: 27–35.) Weitz concluded that art was an open concept, that could expand in order to accommodate new forms of art.

It seems that had analytic philosophers bothered to define the home, they would have come to the same conclusion, for reasons stated above. The home covers too many disparate intuitions for it to be reasonable to expect it to fall under one set of necessary and sufficient conditions. But it does not follow that the home cannot be defined philosophically: it simply needs to be stated that the definitions capture only one version of the home, at one place or one time. And in order to do that, what better strategy than to study what women philosophers of the past have written about the home?

0 Comments

In The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir describes domesticity as akin to the fate of Sisyphus: Legions of women have in common only endlessly recurrent fatigue in a battle that never leads to victory. Even in the most privileged cases, this victory is never final. One could object that there is more to the life of domesticity than just housework: there is also the work of caring for children and other dependants. But Beauvoir also takes mothering into account: Simone de Beauvoir not only thought that domestic work was a form of drudgery, but choosing housewifery, and sometimes motherhood, struck her as examples of bad faith. Women don't really enjoy doing the housework or changing diapers, or if they do, it is because they have forced themselves to stop looking for enjoyment in more rewarding places. Bad faith for Beauvoir meant something different than what it meant for Sartre. Sartre saw bad faith as using one's situation as an excuse for one's life – 'I am a wife, I can only obey my husband' or 'I am a mother, my nature dictates that I should care for my children'. Sartre, rejecting essentialism, believed that one could always choose to react differently to one's situation, except for one odd essentialism of his own: human beings, he thought, were bound to fall into the category of dominator or dominated. Beauvoir rejected this essentialism too: If Sartre thought human beings were by nature doomed to desire domination, then there really was no exit from living our own oppressors. Beauvoir's philosophy, by contrast, refused 'the consolations of lies and resignations' – it was an excuse to think that it's just human nature to dominate or submit. (see Kate Fitzpatrick, Becoming Beauvoir, loc 3475.) This was an ethical disagreement: for Sartre, a woman's bad faith is measured according to her failure to participate in males' projects of seduction (see Toril Moi, 2008, Simone de Beauvoir: The Making of an Intellectual Woman, 150-154). Beauvoir's ethical stance was, like Sartre's underlain by a metaphysical one. Sartre believed that we became free through a situation, that we could realize our freedom by transcending that situation. But Beauvoir objected that women's situations were not and could not be transcended, because they were part of the world that made them who they were, and in many cases, that world made it impossible for them to assert their freedom. Turning away from Sartre's analysis, she went back to Heidegger and the idea that human beings are at one with their world (Mitsein) and to Husserl's phenomenology in order to make it clear that it is the lived experience of women, rather than their situation we need to focus on in order to help them achieve freedom. (see Kate Fitzpatrick, Becoming Beauvoir, loc4298, and Manon Garcia, On ne Nait pas Soumise, on le Devient). So how does this help us understand women's relationship to the home? Women, for Beauvoir cannot simply transcend their situation, nor should they accept them as inevitable: there is something that can be and should done. Resistance to any given aspect of women's lives, whether it is domesticity, motherhood, or subservience, is hard, but not futile, and it involves turning the world around, one meaning at a time. But what singularly defines the situation of woman is that being, like all humans, an autonomous freedom, she discovers and chooses herself in a world where men force her to assume herself as Other: an attempt is made to freeze her as an object and doom her to immanence, since her transcendence will be forever transcended by another essential and sovereign consciousness. Woman’s drama lies in this conflict between the fundamental claim of every subject, which always posits itself as essential, and the demands of a situation that constitutes her as inessential. How, in the feminine condition, can a human being accomplish herself? What paths are open to her? Which ones lead to dead ends? How can she find independence within dependence? What circumstances limit women’s freedom and can she overcome them? The Second Sex, 37. Charlotte Perkins Gilman is best known perhaps for her short story 'The Yellow Wallpaper'. In that story, a young mother, suffering from postnatal depression, is cared for by a loving husband who is also her doctor in a quiet country house. Her husband makes sure that in order to recover, she does not exert herself, does not do anything too stimulating, such as seeing lively friends, or writing; that she rest, that she spends time with her baby (but with the help of her sister in law for any actual work involved caring for the baby). This sounds like a loving and reasonable way to treat someone who is depressed. But at the end of the story, the heroine has lost her mind, thinking that she has been taken over by a woman who'd been imprisoned inside the hideous yellow wallpaper of her bedroom. The story is seminal, in that it depicts clearly and painfully, a malaise that Betty Friedan would later call the 'problem with no name'. Neither the heroine nor her husband are able to articulate what it feels to be her, as a woman suffering from depression – specifically postnatal depression -, and they're stuck with some very unsatisfatory and harmful prejudices, that she needs rest and inactivity, mental and physical, that she will be fulfilled by motherhood, and that she doesn't need anything else in life. Perkins Gilman, when she penned that story, was writing from experience. She too had suffered from post-natal depression, and she too had been advised to rest and spend time with her child in order to get better. Perkins Gilman had in fact visited a famous physician Dr Silas Weir Mitchell, a pioneer of neurology who specialized, among other things, in the treatment of 'hysterical women'. His mission, when treating discounted women was to help become ‘more loving, giving, gentle with her family, and more peacefully content with herself’ through overfeeding and oversleeping. (Mary A. Hill: Charlotte Perkins Gilman: The Making of a Radical Feminist 1860-1896. Temple University Press, Philadelphia 1980, p.148) Perkins Gilman took Weir Mitchell’s rest cure, and of course hated it. Most of her difficulties with motherhood, on top of the hormonal issues that most sufferers of postnatal depression have to deal with, was the fact that she had less time to do the work or the physical exercise she thrived on. Like her aunt Catharine Beecher, Perkins Gilman was a fitness freak, going to the gym daily, taking classes, and running. In an article published in the October 1913 issue of The Forerunner (14 years after the publication of the short story) "Why I wrote the Yellow Wallpaper" Perkins Gilman describes her experience with Weir Mitchell's rest cure: For many years I suffered from a severe and continuous nervous breakdown tending to melancholia -- and beyond. During about the third year of this trouble I went, in devout faith and some faint stir of hope, to a noted specialist in nervous diseases, the best known in the country. This wise man put me to bed and applied the rest cure, to which a still-good physique responded so promptly that he concluded there was nothing much the matter with me, and sent me home with solemn advice to "live as domestic a life as far as possible," to "have but two hours' intellectual life a day," and "never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again" as long as I lived. This was in 1887. I went home and obeyed those directions for some three months, and came so near the borderline of utter mental ruin that I could see over. Virginia Woolf was also prescribed the rest cure, and like Perkins Gilman, she suffered much from the requirement that she not exert herself by doing what she loved best, writing and talking. Whatever the benefits of the cure, it was clearly also designed to domesticate intelligent women and keep them within the domestic circle.

Frances Harper (1825-1911), free-born abolitionist poet and speaker, and Anna Julia Cooper (1859-1964), philosopher and historian born into slavery, both contemporaries of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, also wrote about the home and its place in human progress. Unlike Perkins Gilman, they believed that domesticity was an aid to women's emancipation. Perkins Gilman, a racist, regarded black people as inferior, and therefore did not concern herself with any particular issues that black women might face. Harper and Cooper both argued that black women faced the same problems that white women did, but that as black women, and women who had often been born into slavery, they also faced a number of other issues. Harper, or indeed Cooper, were not merely agreeing with the likes of Catharine Beecher who promoted a difference feminism where women drew strength from the good management of home and children. [1] For Harper and Cooper, part of the defense of domesticity was aimed at the betterment of the life conditions of the black people of America. In a letter to a Philadelphia correspondent, Frances Harper wrote the following: While I am in favor of Universal suffrage, yet I know that the colored man needs something more than a vote in his hand: he needs to know the value of a home life; to rightly appreciate and value the marriage relation; to know how and to be incited to leave behind him the old shards and shells of slavery and to rise in the scale of character, wealth and influence. Like the Nautilus outgrowing his home to build for himself more 'stately temples' of social condition. A man landless, ignorant and poor may use the vote against his interests; but with intelligence and land he holds in his hand the basis of power and elements of strength. (William Still, The Underground Railroad, 1872). Part of Harper's concern is with men and drinking: as a temperance activist, she fears that the whole human race is at risk of hereditary depravity and that black people, more vulnerable to social ills because of their recent insertion in free American society, are particularly to be protected. A good home, where you can come home to after a day's work, where you can be happy surrounded by a loving family, and where churchgoing and bible reading are common pastimes, is the best remedy against alcoholism. She also knew from her own experience that it is hard for a black female to maintain a home without a husband. Having lost her own husband to premature death, she found herself kicked out of her home, all her possessions reclaimed. "I did not feel" she recalled in a 1866 talk to a National Woman's Rights convention in New York, "as keenly as others, that I had these rights, in common with other women, which are now demanded." Notwithstanding the above considerations, the passage cited above may strike one as a little moralizing: why should the home be a priority for someone who has had no freedom of movement, someone who was forced to live and work on the land of a man who had the right to beat them, rape them or sell them? Why should such people, upon becoming free, seek to live in the way of their oppressors, adopting the same notions of respectability, the same structures and the same values? A slightly more nuanced interpretation is needed here. We saw that in any case Harper's arguments came from a different position than Beecher's and the American cult of domesticity. Her position takes into account the lives of black men and women, their attempts at making a place for themselves in American society, and the backlash they were confronted with from people who'd agreed they should be free, but nonetheless did not want them to live among them as equals and looked for every opportunity to show that they were not. So a non-domesticated, alcohol addicted black man, was not just that, but also an indictment against all black men and women. On the other hand a home meant a way of entering society from a stable position, that is not only a home, a church, but a school district, a job, shops and access to medical care. For that reason it is wrong to read Harper as moralizing even if we can question her actual allegiance to the value of domesticity. Cooper's vision of domesticity is, perhaps more obviously than Harper's, a feminist one: domesticity empowers women, it enable them to put their particular strengths and virtues to practice for the betterment of humanity. A stream cannot rise higher than its source. The atmosphere of homes is no rarer and purer than sweeter than are the mothers in those homes. A race is but a total of families. The nation is the aggregate of its homes. As the whole is sum of all its parts so the character of the parts will determine the characteristics of the whole. A Voice from the South, Dover Thrift edition – 11. The home is essential to the nation. Until black people have homes which are well run by educated women, they will not be in a position to take up their full and rightful place into American society. That women are essential to this process is clear from the fact Cooper says they must be educated: this is in part because their principle task as home-makers is the training of children 'a task on which an infinity of weal and woe depends. Who does not covet it?' - 8. Cooper is in some sense a perfectionist, who believes that happiness lies in the progress we make towards evolving goals, not in the achievement of perfection.[2] We need to be active in our pursuit of these goals, and indeed in the setting of them in order to flourish. And education, the higher the better is a large part of that process. In order for black Americans to partake and participate in the general flourishing, they need homes where future generations will be shaped. And for that to be successful, she argues, black women must be educated. So domesticity Cooper argues, as it requires educated women, can help emancipate women. Notes

[1] For Beecher, women derived power specifically from domesticity: '[Woman's] true position in society, as having equal rights with the other sex; and that, in fact, they have secured to American women a lofty and fortunate position, which, as yet, has been attained by the women of no other nation.' 35Treatise on Domestic Economy, Miss Catharine E. Beecher, Boston: T. H. Webb, & Co.1842 [2] She cites Stael, on p.2: "Happiness consists not in perfections attained, but in a sense of progress, the result of our own endeavor under conspiring circumstances towards a goal which continually advances and broadens and deepens till it is swallowed up in the Infinite". I could not trace the original. Social philosopher Charlotte Perkins Gilman, a contemporary of Shaw – Judith Allen said that 'she is the Bernard Shaw of America; or should we say that Bernard Shaw is the Charlotte Perkins Gilman of England?' (2009, 2) – wrote that : every human being should have a home. The single person his or her own home; and the family their home. […] The home should offer to the individual rest, peace, quiet, comfort, health and that degree of personal expression requisite; and those condition should be maintained by the best methods of the time Unfortunately, Gilman goes on to argue in The Home, Its Work and Influence, these conditions do not in general obtain for most people who do have homes. Homes as they were in nineteenth century North America did not provide much for children, especially in terms of health, education or personal development, no peace, rest or comfort for servants, who lived in a house that was not their home, but that of their employers, and very little for women, for whom the home meant first and foremost confinement, and domestic labour. The myth of the home, Gilman argued, was a dangerous one, which not only perpetuated misery for many, but also obscured the importance of the public sphere, in particular places of learning, for human progress and wellbeing.

The home, for Perkins Gilman, was a necessary part of human flourishing, but a very different institution from what it was perceived to be in the era of the Cult of Domesticity, where women were perceived as angelic creatures, making the home a place of health and virtue by drawing on their natural feminine character: nurturing, patient, and pious.[1] So Perkins Gilman believed everyone ought to have a home, but not a 'home' in the full sense understood by many. Insofar as her work is a critique of the existing understanding and realization of the home (in early 20th century USA), it does not consider whether the home is in fact necessary for human fulfillment, and whether other ways of living might not work as well, or indeed better for some portions of the population, such as communal dwellings, movable monadic dwellings, or a series of temporary dwellings, whether hotel rooms, or the home of friends and family members, or indeed dwellings provided by the work place. Yet nor does Perkins Gilman deny that these non-traditional (if tradition is late nineteenth century, early twentieth white, middle class America) types of home can bring about flourishing. In fact, her central argument, that the home's main function should be to complete and support the framework supplied by the states' institutions, in particular educational ones, would seem to favour a more minimal approach to the home. In that sense, Perkins Gilman's picture is very Athenian: it is the public life that shapes us and ensures our flourishing, the city is responsible for educating its citizens, and organizing their lives so they can make the most of what have. The role of the home is simply to keep us warm, fed and rested in between excursions to the public forum. The main problem presented by the home, for Gilman, is that the home, such as it was at the time she wrote, fails to do even that, that it, it fails to keep its citizens healthy and safe. The American home, she says, exercises too much control over the health, nutrition and education of its inhabitants, with too little qualification to do it well. Home cooking, she says, is not by its very nature superior to food that be bought in restaurants or hotels – it is simply more convenient for feeding the young, but at the same time keeps a woman tied to her home. But unless each home cooking woman is educated on healthy diet and food preparation, there is no reason to think that home cooking will be anything else than 'slow-poisoning' of our bodies, resulting in 'Dyspepsia' and 'false teeth before they are thirty' (chapter 8). As far as safety of the young is concerned, she says, houses which serve as homes are not in fact designed with the safety or well-being of children in mind, they are out of scale for them, and inhospitable and dangerous. Because parents are not trained in the treatment of childhood ailments, she adds, when homes are considered the best place for a child to grow up, mothers will simply transmit and perpetuate the mistakes that were committed on them as a child, resulting in ill-health but more generally stunted development of children (ch. 12). Finally, she argues, the home, no matter how good a home it is supposed to be, cannot provide enough in the way of social progress, it cannot train citizens, nor make them fit into the society they are meant to help build or improve, if children are under the control of the home during the period where they should develop, and all their lives, if they are women. What is most problematic about the home then, according to Gilman, is not only that it fails to keep its inhabitants safe, but that at the same time it blocks their access to the educational, health and civic resources that they would need in order to flourish and to contribute to human progress. The image of the home as the place where we can live safe, happy, and in privacy; a place where we can retreat from the world and at the same time be educated to live in it, she claims, is both a fundamental to what we understand the home to be, and deeply flawed. There is a feeling, she says, that 'home is more secure and protective than anywhere else', and that feeling, she claims is at the heart of whatever myths we still believe about the home. These myths, she concludes, must be dispelled, and the home must open up to social progress, and change to accommodate our real needs as human beings and citizens. What shape should the new home take? Gilman doesn't say. But we can derive some possibilities from suggestions she makes. First, she points out that all homes are built according to a model that is nearly identical, and in particular, that those homes that are deemed unsuitable for families by landlords, are the very same as those in which families do live. So perhaps she would argue that families with children need to live in different sorts of buildings than families without children, and that these choices should be made not according to income size, as they mostly are, but need. Secondly, she points out that we may be better off in many cases eating out than cooking in. And her arguments that women become slaves of domestic work seems to suggest that she would be a fan of take out dinners (though perhaps not daily pizza). Simone de Beauvoir, drew a similar conclusion, bypassing the question of health (perhaps because French restaurant food at the beginning of the century was no less healthy or balanced than what people prepared at home), when she pointed out that single working women often made life more difficult for themselves, compared to their male colleagues, by insisting on cooking their own meals instead of eating out at conveniently located restaurants and hotels (vol 2, part 4, ch 13, 593.) The point is that not all homes need kitchen, not all home-cooked food is better, and very little home-cooked food is better than the freedom of not having to cook everyday for your entire family. Kitchens are also dangerous places, where knifes and heavy objects are kept, intense heat, and of course, germs, which require constant and intensive cleaning. The very realization that home life does not necessarily requires cooking may change our expectations as to the shape of the home. Unless cooking is something that is essential to one's flourishing, unless someone enjoys spending time preparing food on a large scale, there is not much need for a kitchen in a home. A kitchenette is sufficient, such as may be found in a trailer home, or a shared kitchen, as in students halls, or, if you don't cook at all and you live alone, a hotel room (which is Beauvoir's own recommendation) is even better, as you will not be required to do any housekeeping, but will be guaranteed a clean place to sleep every night, and somewhere safe to keep your things. Perkins Gilman, as we saw at the beginning of this section, does not claim that we do not need homes. Rather, she argues for a twofold position. First, the home as her nineteenth century readers knew it, was harmful both because it didn't provide a safe or healthy environment for its inhabitants, but also because it promoted itself as an ideal, which could not and should not be modified. Secondly, she recommended that we recognize the cult of domesticity for the harmful myth it was and start thinking in terms of modifying the home, adapting it to a less dominant but still essential role, that of supporting human beings in their quest for flourishing in society. Taking up where Perkins Gilman left off, we can now ask whether the home, in this minimal role, must still resemble in any way what we now think of as a home. When Eliza Doolittle in the musical version of Bernard Shaw's play, Pygmalion, first appears on screen after her altercation with Professor Higgings she is singing 'All I want is a room somewhere'. What she wants, it seems, is a place of her own, where she can sit down after a day's work without having her earnings taken from her, or without being shoved out of the way by parent, step-parent, or sibling – and where she can eat chocolate. But the smiling face of Audrey Hepburn, together with the Technicolor quality of the film suggests that she wants something more: a home with a family of a her own, a home where she is no longer poor, and no longer has to go out to the streets to work, but can be a proper, respectable woman. At the end of the play, she has achieved some of this: she has a home and a flower shop with a husband she has chosen for herself. However, she has disappointed her maker, Professor Higgins, who would have liked to keep her to himself, offering her his home to share (why doesn't she just move her husband into her room on Walpole street, as she would a piece of furniture?), or indeed her writer, Shaw, who suggests, by telling us how both her marriage and her business turn out to be unprofitable, her choice was a mistake, not ambitious enough – she has failed to achieve independence, to fly away, and insofar as Higgins was the one charged with bringing her to life, it is also his failure. Eliza has settled down, and she has settled down, after all the promise of her transformation, for very little – she lacks enthusiasm about her husband and her job, and is perhaps more concerned still with the lives of Prof Higgins and the Colonel than with her own. On the other hand, she has successfully escaped from the (tyrannical) meddling hands of her father and Prof Higgins, and that was perhaps the best chance for independence she had, figuring out that it was harder to interfere with a married woman than with a single one. Having her own home, away from Walpole place, meant that she had a chance at becoming her own person, even if she had fewer tools at her disposal for self-development. Where, in the coming to life of a character, the reaching for independence, should the getting of a home figure? And why should it figure at all – can one not break away from interference without settling (as indeed, Eliza's sister in law, Clara, ends up doing)? Can one not be a fully developed human being without having a home? The question is fraught, not just because of the enormous power the idea of the home has on us, but because depending on our answer, we may exclude ways of flourishing that do not fall within the 'domestic norm', or at the very least, marginalize them, because we think that domesticity is the key to human growth and flourishing. And this is what I'm going to be working on, so watch this space! |

AboutThis is where I blog about my new book project (under contract with OUP): a history of the philosophy of the home and domesticity, from the perspective of women philosophers. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed